Walking around Montreal, people-watching, one would find it hard to tell by their faces, dress or demeanour whether these passersby were born here, and - if not - when they arrived, how much at home they feel, how easy it is for them to melt into this sea of diversity. Some never even wonder about it: multiculturality is a face of Canada that's natural to them, expected. I always wonder about it - because I'm still a new immigrant.

Canada is a country built on immigration, with 95% of its current population non-aboriginal, a strong testament to how people can make a new start in this place, no matter the circumstances of their arrival. Over time, and notably toward the end of last century, it has started regulating its immigration practices, with a view to supporting and promoting multiculturalism. It is no wonder that around 250 000 people arrive every year, ready to make this place their new home.

Among Canadian provinces, Quebec holds a special place due to its strong Francophone culture. Surrounded by Francophony, Montreal is of Quebec and still different, a cosmopolitan and diverse city. Of the approximately 50 000 yearly new residents in Quebec, 35 000 land in Montreal, and the obstacles they have to face in order to get to function in this society are typical of its particular intersection of culture, language and economy.

I talk to people about immigration and integration on an almost daily basis. Most of the immigrants who've crossed my path recently are highly educated and chose to come here as adults - on paper, they are the model residents that Canada, and Quebec, are looking for. After 2 to 5 years here, it is clear that these people want to settle, so, how far along have they come? In their hierarchy of needs, once they have solved the basics, what other problems rear their heads, and are these problems more and more Canadian as time goes by?

***

There is no denying that there are a lot of programs and organizations in Montreal working towards facilitating the integration of newcomers. On the other hand, the requirements made on newcomers here are harsher than elsewhere: learning a new language on top of equivalating one's education and coming to grips with a social environment that is strongly polarized and where it seems like the Allophones, in spite of their more and more visible presence, still have little to say.

Finding work is always the hardest part of moving to a new place. The unemployment rate for Montreal in 2014 was of 11.3% among the immigrants, compared to 7% for the city overall; this despite the fact that almost 60% of the immigrants to Quebec have completed at least 14 years of schooling, and a majority of the well-educated ones choose Montreal as their destination. All across Canada, the unemployment gap between immigrants and Canadian-born workers is biggest for those with the most education ( 4 to 1 in 2014) and Quebec has generally had worse immigrant unemployment figures than most other provinces. Currently the province is attempting an upheaval of its immigration policy based on the specific necessities of the job market and a tightening of the language requirements, but for the newcomers who have already made it in it`s still an uphill struggle.

The standard guide to integration a new resident gets on entry recommends attending Emploi Quebec workshops. These are 7 or 8 sessions of instruction which give the participants basic information and training on life and work in Quebec, ranging from getting warm clothes for winter to knowing how to introduce oneself to potential employers. A major advantage of these courses is that they alert newcomers to opportunities, such as the option (for residents who arrived less than 5 years ago) of being matched up for an internship with an entreprise in their field.

Amiee H., 36, an American who moved to Montreal in 2013, sponsored by her Quebecer partner, is a textbook example of perseverence in this respect. After completing Francisation in 2014, she took any internship that was on offer: "I attended a 3-day training for Human Resource professionals with the Board of Trade, a 4-week training with the Club de recherche d'emploi Montréal Centre-Ville and a 4-week internship with the Interconnexion program offered by the Board of Trade of Montréal. I also completed a one-month unpaid internship with Quantum Staffing Services, in hopes of [acquiring] the Canadian experience I needed to get a job."

It was through the Interconnexion internship that Amiee found her first and current job as an Assistant-H.R. and Administration, more than one year after arrival, which is still remarkably quickly. Common wisdom may say it was easier for her as an American, because the transition is not as abrupt - but Amiee did immerse herself willingly into a foreign culture, bringing positive attitude and determination to the process. She commends the spirit of hard-working self-reliance in which she was raised by her parents, Mexican immigrants to Texas themselves.

***

Amiee is lucky to have landed a first job in her field. Apart from the few whose qualifications are in demand, it is mostly assumed that immigrants will hold different subsistence jobs before they get themselves on their feet. "I think the biggest challenge for me is patience, because to get where you want to get you need to do a bunch of things that usually take a lot of time," says Claudia P., a language teacher with an MA in Education, who arrived in 2009 from Colombia. For example, it takes at least a few months for the newcomers' study diplomas to be equivalated according to Quebec standards, not to mention that some degrees may not be recognized, or may need to be completed. Claudia obtained her first job, in a kindergarten, 6 months after arrival, through Emploi Quebec; more than a year later she started teaching Spanish part time for the Montreal School Board, and is now studying to complete a certificate in teaching English, which would widen her job opportunities.

In the same evening classes in the TESL program at Concordia University I met Blagovesta K., who arrived in 2010 from Bulgaria, with her family. Her first Canadian job, obtained through a friend of a friend's, was in a call center. She has more than 10 years' experience teaching English in her native country, but finds breaking into the job market here intimidating and hopes that Canadian certification in her profession would help pad her résumé. One of the draws of Quebec in this respect is very accessible education costs for residents in the province, supplemented by financial aid which allows a lot of newcomers to buy a little adaptation time through pursuing full-time studies. It is an enormous investment and at the same time a gamble - both for students, who put in time and effort without having guarantees of employment, and for the province, which is spending money to groom specialists that might well decide to move to other provinces with their degrees, especially in fields like Teaching English.

***

The importance of the French language is paramount in both the professional and social life of Montreal. Talking about challenges she faced in adaptation, Amiee remembers: "I was told my French was not good enough [...] which prevented me from obtaining a first job, even jobs that I was over-qualified for."

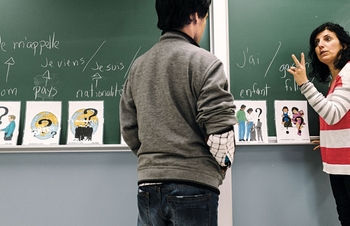

According to recent statistics, 43% of the newcomers to Quebec do not speak French at all upon arrival. French language courses are offered for free or almost, to new residents who can afford to take time and sit through them either full time or in evening classes. For many, irrespective of the type of work they are looking for, learning French means a commitment to Quebec values, which they undertake willingly.

Some, like Amiee, who have a partner's support and aim for good jobs off the bat, have attended Francisation full-time, systematically. Others, like Blagovesta, have taken some time off it, returned and retaken some levels. A lot of newcomers are financially pressed to start working right away, and, together with the stress of adjustment, taking French classes often proves too much of a burden. But there is proof that when one sticks with the program, benefits will follow. Alejandro R., 40, arrived from Mexico in 2009, managed to finish his 6 levels of French in night classes over the course of 2 years, while holding a day job in a shoe factory. He had a degree in IT from his country and knew the language would be a stepping stone towards a well-paid job, which soon proved to be the case. Emboldened by this success, in 2012 he started an MA program in French at Université de Montreal, which he counts on to lead him to further career advancement. His girlfriend, whom he met here, is a Quebecer, so most of his life does happen in French, a sign of successful integration if any.

***

In conversations with newcomers, finding out your interlocutor's status can be a surprise. I started questioning M. L., 35, about her work and life in Montreal knowing she arrived less than 2 years ago from South Korea, with her husband, and she works in IT (as a 3D artist, doing augmented reality implementation) - only to find out that she had been unemployed until last October, filling her time with sending CVs and taking French classes for 6 months at a language school. "Why didn't you go to Francisation?" I inquired - "Oh, my husband and I had no permit. If I want to take the class, I should hand in work permit papers." So...she is not a resident yet? - "I'm nothing here," M. says disarmingly, but "we are progressing." She and her husband first arrived as tourists, on a 6 month visa. The fact that she is now working in her field has enabled them both to start their residency application, and they will wait for the response from here; by the time they become residents, their integration will be well on its way.

In my 5 years here, I met a lot of people who, like M., hope to change their limited visas into a Canadian residency. Some apply to be sponsored by Quebecer spouses, and can stay on as tourists while their files are being processed. Of course, this precludes access to legal jobs, health care, or to education at the much lower tuition costs paid by provincial residents. French schools also only cater to residents, refugees or workers, not to "tourists", though these actually need to learn French in order to support their applications.

***

When it comes to genuine social interactions, during their first years immigrants will mostly meet other immigrants, owing to their specific priorities and circumstances. While this still counts as making their place in the city, it keeps them somewhat isolated from Anglophone and Francophone circles. Alejandro, Amiee and Claudia have all made their first "Canadian" friends in Francisation, though with the rigours of their respective new job and studies they don't have much time for socializing any more. The work or school environment may help diminish the cultural gap or, on the contrary, reinforce it at first. "I think it will just take time getting used to the way people interact with each other," says Amiee. "Back home, I was able to read between the lines during conversation and I understood body language and tone of voice. Here, I never know when someone's joking, when they're being sarcastic and when serious. This is something I encounter mainly at work."

While unemployed, M.L. has relied a lot on meeting people through local meetup groups. Her main group of close acquaintances in the city labels itself a gathering of "international women", the word "immigrant" (with its implications of hardships and obstacles) not even mentioned; the membership is diverse, including newcomers, temporary workers from European French-speaking countries and women born in Canada who value their second- or third-generation ancestry. These friends have been a great help to M., advising her in her job search, on making cold calls and going out in person to companies instead of just dropping her CV, which has been instrumental in her getting her first job opportunities. Moreover, they have helped her think of Montreal as a welcoming place, where she has chances of fitting in.

"I am as integrated as I could be," concludes Claudia, matter-of-factly, after more than 5 years here. "I have a job, I have adapted myself to the Canadian, and more specifically, to the Quebecois way of life, and so far it's been trauma-free. However, even if I am Canadian now, I know I'll never be a true Canadian; I speak, think, do things differently. What's missing [here for me]? family or a tighter support system."

Blagovesta says that friendships, apart from some Bulgarians she knew from before moving, have been almost impossible to make: "We don't listen to the same music, eat the same food, discuss the same topics. I see that people are not interested in my culture, they expect me to be interested in theirs. Friendship and interest has to be mutual." Still, she notices a change in her attitude compared to immediately after arrival: "In the beginning, I tried hard to assimilate, become Canadian - then I realized that everyone has their history, and I can just be Bulgarian-Canadian, which is what I am anyway."

Photo credits:

(1) Montreal as seen from space http://spacing.ca/montreal/2011/01/10/montreal-as-seen-from-space/

(2) http://www.agoracosmopolitan.com/news/lifestyles/2011/12/28/2454.html

(3) http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/406769/le-francais-c-est-l-inclusion

(4) Revolutions by Michel de Broin, next to Papineau metro, Montreal

http://weburbanist.com/2010/09/27/stairs-to-nowhere-15-works-of-surreal-staircase-sculpture/

Sources:

http://www.immigration-quebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/settle/montreal.html

Best Settlement Practices, Canadian Council for Refugees 1998 http://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/static-files/bpfina1.htm

http://globalnews.ca/news/1074811/immigrant-unemployment/

Personal interviews, February 22-25, 2014

Leave a comment