Welcome to Canada! Now Integrate

Immigration is a recurrent issue in countries around the

world. The meeting of the host country's and the immigrant's cultures and

languages can sometimes cause conflict as nationalisms flare up and cultural

and linguistic protectionisms kicks in. An interesting phenomenon is that of

the more recently founded nations like those of the Americas. For some

countries, like the United States, there is less emphasis on official

multiculturalism and more of a tendency to regard the ensemble of citizens as

being simply American. For other countries, like Canada, there is an emphasis

on multiculturalism and on encouraging cultural diversity... that is, officially.

Immigration is a recurrent issue in countries around the

world. The meeting of the host country's and the immigrant's cultures and

languages can sometimes cause conflict as nationalisms flare up and cultural

and linguistic protectionisms kicks in. An interesting phenomenon is that of

the more recently founded nations like those of the Americas. For some

countries, like the United States, there is less emphasis on official

multiculturalism and more of a tendency to regard the ensemble of citizens as

being simply American. For other countries, like Canada, there is an emphasis

on multiculturalism and on encouraging cultural diversity... that is, officially.

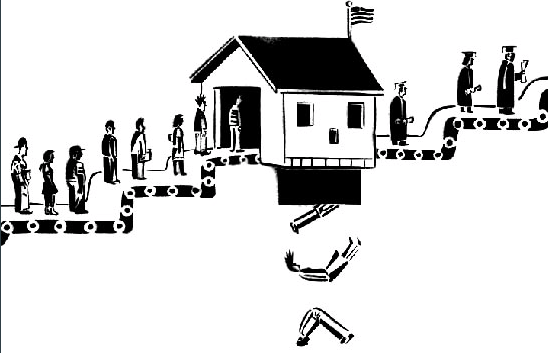

One of the groups most affected by policy on immigration and integration is immigrant youth, who must toe the line between solidifying their emerging cross-cultural identities and fitting in both at school and in the larger society. That educational institutions play a significant role in the lives of immigrant youth, both as primary places of socialization and as spaces for obtaining the linguistic and cultural knowledge necessary to their success, is undeniable... But can Canada continue to preach multiculturalism while essentially promoting cultural and linguistic conformity and homogeneity through intensive educational integration programs for these youth?

To answer this question and briefly assess the programs in place, this paper will examine several aspects of the issue. First, an overview of Canada's historical relationship with immigration and multiculturalism will be helpful in providing a framework within which to judge the merits and shortcomings of the current related educational programs. Second, a look at the statistics on immigration and the linguistic demographics of Canada will facilitate an assessment of the importance of this issue from a purely quantitative perspective. Third, a detailed portrait of the needs of new immigrant youth and of the systems in place to respond to these needs (within schools) will reveal both the positive and the negative aspects of current programs. Finally, a few of the changes that have been suggested by experts in the fields of education and immigration policy will be helpful in presenting solutions to several of the main problems in the current discourse and programs.

The Canadian education system: division of powers

The accommodations provided through government programs to new immigrants are largely federally mandated, and provinces generally do not have much say in immigration policy. One area of legislation affecting immigrants that provinces do control is education. As many new immigrants must learn English or French upon arrival in Canada, there has been an integration of language programs within mainstream schools, as well as course material within these programs that promote the values and norms of Canadian society.

As outlined by the Council of Ministers of Education Canadian Commission for UNESCO in 2008, the Canadian education system is organized as follows:

...In the 13 jurisdictions -- 10 provinces and three territories -- departments or ministries of education are responsible for the organization, delivery, and assessment of education at the elementary and secondary levels, for technical and vocational education, and for postsecondary education... (7)

Each province has unique cultural and linguistic issues it must address and consequently, provinces tend to incorporate a diverse array of programs and services for the equally unique needs of whatever particular demographics they must respond to.

Multiculturalism in Canada

The concept of multiculturalism is central in shaping educational integration programs. In immigration policy, multiculturalism is a term that has greatly evolved over the last century, reflecting the Canadian government's changing relationship with immigration.

Since confederation in 1867, Canada can be said to have witnessed three distinct waves of immigration. As outlined in Allan Gregg's article "Multiculturalism: A twentieth-century dream becomes a twenty-first-century conundrum," the first of these waves, from the early twentieth century up to World War Two, was predominantly made up of white, eastern Europeans.

The second wave came in the aftermath of the war when Canada once again began to accept new immigrants. Both of these two first post-confederation waves of immigration were strictly limited to whites:

As is reflected in the 1952 Immigration Act, entry into Canada was deemed a privilege and individuals could be barred based on ethnic affiliation. Immigration was now clearly controlled through country- of-origin quotas, which actively restricted non-white immigrants and implicitly validated the notion that nation-building requires assimilation." (Gregg, 2)

The third wave of immigration was defined by the end of the whites-only policies of the past and the ushering in of an era of what Gregg calls the "meritocratic" points system still in place today (Gregg, 2). Non-whites were now able to immigrate to Canada, necessitating, along with a number of other factors, a revamping of the notion of diversity.

Thus was born Canada's image as a nation embracing multiculturalism, a concept defined in the 1988 Multiculturalism Act as: "...[reflecting] the cultural and racial diversity of Canadian society and [acknowledging] the freedom of all members of Canadian society to preserve, enhance and share their cultural heritage..." (3.1.a) The act also requires the "... [advancement of] multiculturalism throughout Canada in harmony with national commitment to the official languages of Canada..." (3.1.j), because the act was meant to appease separatist sentiments in Quebec by making French an official language and by recognizing the Quebecois as a founding people of Canada. (Gregg, 2)

Integration

As outlined by Peter Li in "Canada's Discourse of Immigrant Integration", the term "integration" is used by scholars, policy makers and immigration critics mostly to reaffirm Canada's "... monolithic cultural framework that preaches tolerance in the abstract but remains intolerant towards cultural specificities deemed outside the mainstream." (Li, 1)

According to the findings of the 2006 Canadian census, immigrants make up almost 20% of the Canadian population, without counting non-status people and so-called second-generation immigrants; linguistically, 20.1% of the population is made up of allophones ("Immigration in Canada").

Despite the fact that immigrants make up an increasingly significant portion of the Canadian population, there is still a tendency by critics of immigration and by reactionary political conservatives to see Canada as the white, predominantly Anglophone European confederacy of yesteryear. This reaffirms the problematic perception of new immigrants as challenging, by their very presence, the overarching values of such a society (whatever those may be).

One area in which the above-mentioned contradiction is most obvious (despite the government paying lip-service to Canada's respect and recognition of the unique contributions that newcomers can make) is the non-recognition of professional competencies for adults and of prior learning for children and adolescents. This reveals the underlying assumptions that so called first world countries make about the legitimacy of other countries' education systems and professional certifications. This is an obstacle not only for the educational and professional advancement of new immigrants, but also to their developing a sense of belonging to their host culture. In dismissing and diminishing the legitimacy of their countries of origins and those countries' institutions, Canada ensures that newcomers will be more prone to retreat into so-called ethnic enclaves that reinforce and respect the so called "heritage" linguistic and cultural identities that their hosts reject.

What is educational integration?

The purpose of educational integration as outlined by the Quebec ministries of Education, Relations with Citizens, and Immigration, in their policy statement "A School for the Future", is twofold: to impart to immigrant youth the values and norms of the host society, and to ensure the "...accommodation of ethnocultural, linguistic and religious diversity." (5)

One can see how education would play a crucial role in the assimilation or inclusion of new immigrants into the larger Canadian society, particularly new immigrant youth. It is the first space in their new lives dedicated in part to socialization, both in the sense of acculturation and in the sense of interacting with peers. It is also, especially in the eyes of the newcomer, a microcosm of the larger society.

These spaces of socialization are, for some, useful transitional spaces that help them to better navigate their host country. For others, they are an indication of how they are to be mistreated by their so-called hosts, Canadians.

Immigrant youth of color

Although most newcomer students encounter some degree of hostility and tend to have trouble fitting in with their Canadian born peers due to linguistic and cultural differences, some groups fare worse than others.

The new immigrants who seem to fare particularly poorly in school settings are immigrant youth who are members of a visible minority. Accounts of name-calling, physical confrontations and general social isolation by these youth can be found in numerous studies (see Allen, Khanlou, Steinbach).

This brings up the question of otherness and social status. If the integration that school programs intend for immigrant youth focus on teaching newcomers language proficiency and how to find a place in the host culture, what is lacking is true social inclusion within the student body for those whose appearance will always betray their origins. This experience is not limited to new immigrants, as voiced by an Iranian first generation immigrant youth of the experience of a Canadian born friend:

So where are you from?, she goes, 'I'm Canadian', the other person goes 'no, where are your parents from?, she's like 'no, they were born here too', they go 'oh, how about their parents?', ... how far are you going to go back just because they look like an East Asian?" (Khanlou, 503)

To be truly Canadian, then, is not an option for immigrant youth who are members of visible minorities, at least, as long as the perception of Canada as a white European colony doesn't change or at least evolve.

Educational integration programs for immigrant youth

Although there exist programs and organizations in the larger community that provide support to immigrant youth, a serious lack of funding and structure undermines their effectiveness and accessibility (Van Ngo, 86-92). There is therefore a need to acknowledge the role of schools as the primary and arguably the most important sources of support and encouragement for these youth. Quebec's Accueil program and Ontario's ESL/ELD (English as a Second Language and English Literacy Development) programs are two examples of provincial programs that seek to provide the necessary services to immigrant youth within the school system.

Quebec

As outlined in "Educational Integration or Cultural Segregation? Examining Quebec's Accueil System", Quebec is, in fact, rather unique in its history of linguistic protectionism: "...protectionist policy aimed at preserving the French language and Quebecois culture [has] affected institutions...With the advent of Bill 101... only children with at least one parent educated in an English school system [are] allowed to attend an English school." (Mariekebw, 2)

This preoccupation with the preservation of the distinct Quebecois language and culture has brought about a political environment in which immigration is seen as a mixed blessing. New immigrants, with their own cultures, religions and languages in tow, pose a dilemma for proponents of the language laws of the province and for those concerned with protecting Quebecois culture from assimilation by the dominant "Americanism" (a term used to describe the encroaching, predominantly American, English language popular culture). Born of this complex socio-political context is Quebec's Accueil program. The program is "...an intensive host-language learning bath as prerequisite to entering the mainstream... intended to be a one-time, 10-month intensive linguistic preparation for mainstream classes... accueil programmes are [therefore] intended to prepare their students to enter all mainstream classes." (Allen, 5)

Although Accueil is meant to last ten months, if students do not pass standardized tests by the end of the ten month period, they are required to repeat the program. This has lead to feelings of inadequacy and has undermined to confidence of students used to having above average academic performance in their countries of origin (See Allen, Steinbach). The program is meant to facilitate integration by getting the issue of host language proficiency out of the way before expecting students to perform efficiently in mainstream classes, but it has proven instead to be an obstacle for many participants.

Ontario

Ontario, on the other hand, offers a range of options to the new immigrant student in terms of linguistic support and instruction. There are three main options and students are placed according to language proficiency and previous level of education, as well as the resources of the school. The most popular method involves integration into mainstream classes with some linguistic support offered outside the classroom. The second method is similar, but involves having an ESL teacher on hand in the classroom. This method would be the most helpful in schools with large immigrant populations. The third method is similar to Quebec's Accueil program and is the least popular, reserved mostly for students who have little educational background and very little proficiency in English. (McAndrew, 1534)

The methods are often combined depending on the needs of the students and the resources of the schools, but some experts argue that the lack of structure in these programs allows schools to employ insufficient numbers of qualified language instructors and other appropriate educators while spending the budget for these programs to cover unrelated expenses (Van Ngo, 92).

Advantages and disadvantages of Accueil and ESL/EDL

Both of these approaches have been criticized. On the one hand, the Accueil system can be said to be outdated, isolating, and reminiscent of racial or cultural segregation within schools. It must be said, however, that Ontario schools also use this method of intensive linguistic immersion for certain students, and that the unfortunate aspects of these programs are surely not intended to create a segregated student body.

On the other hand, Ontario's approach has been criticized as being a way of ducking the responsibility of implementing an across the board program which would require committing more resources to schools. (McAndrew, 1534-39)

One of the best indicators of the success of these methods is the evaluations of the students themselves. Students in both provinces share some general critiques, such as the inefficiency of standardized language tests in both placement and evaluation (see Liying on ESL testing). Another common critique addresses the strained relationships between immigrant students and the rest of the student body; yet another, the discrepancy between acquired colloquial language and linguistic curriculum.

There are, however, major differences in the experiences of new immigrant students in Quebec and those in Ontario. Starting with Quebec, there is one important criticism of the Accueil program that keeps surfacing in the literature, namely the social isolation experienced by its participants. Articles by Marilyn Steinbach and Dawn Allen draw on student testimony to bring this problem to light. In Allen's "Who's in and who's out? Language and the integration of new immigrant youth in Quebec" she interviewed eighteen students who were representative of the diversity of the program's participants at that school. (Allen, 257) Many of these students were disappointed in failing to complete the Accueil program within the first year and therefore being denied access to mainstream classes for up to another year. They felt not only that they were falling behind academically, but that their performance in Accueil was somehow indicative of their potential academic performance in the Canadian school system. (Allen 257-259)

Similarly, students in Ontario schools report feeling as though they are more easily integrated into peer groups that share their cultural background, religion, or ethnicity, a trend that reflects the so-called "ethnic-enclaves" in the larger society. (Steinbach, 100)

Solutions

Many solutions and improvements have been posited by experts in the fields of both immigration and education to the problems of current educational integration policies and practices. Although all suggestions that may improve the experiences of immigrant youth and inform schools' attitudes towards cultural and linguistic pluralism should be considered, there are a few that seem most relevant.

The first would be the continued and increasingly popular integration of so-called heritage language programs within schools. Offering new immigrant students the opportunity to continue studying in their language of origin while acquiring host language skills in immersion programs may actually improve overall academic performance. There is some evidence that proficiency in and knowledge of the fundaments of one's heritage language may facilitate the learning of a second language. (McAndrew 10-12)

Another important measure would be ensuring the adequate training of the educators teaching these programs. As we saw in the Ontario system, not implementing a clear framework with competent professionals available to students in need can create a perception of structural insecurity and may actually deprive students of proper access to said professionals.

The final issue that must be addressed is the correlation between students' socialization and their motivation to apply themselves academically. As witnessed in Marilyn Steinbeck's study, being excluded or isolated from the rest of the student body can have a detrimental effect on students' emotional well-being and may affect their overall academic performance by undermining their confidence.

Conclusion

Educational integration and integration of immigrants in general, will cease to be an issue the day that "otherness" ceases to be viewed as somehow incompatible with pre-established norms and values. Unfortunately, it is unlikely that there will be widespread acceptance of the fact that all cultures are the products of gradual evolutions in values, norms, religions and languages. Language itself, a major contentious issue as we have seen from the Quebec examples, is an evolutionary process that is more multicultural than any country, with its mish-mash of historical influences, yet peoples of the world continue to insist on "preserving" languages, much like countries attempt to preserve their so-called cultural integrity by forcing immigrants to adopt homogenous cultural identities.

Failing to strive to truly realize what is commonly referred to as Canada's cultural mosaic would be a great loss for all concerned. Perhaps it is some psychological historical memory that complicates this process, some fear that those who land on our shores will become the violent pillagers that the founders of the Canadian territories were to the indigenous peoples. Perhaps it is not so much a memory but a reality, one that nationalists around the world keep perpetuating, that there is one supreme culture, one supreme language that trumps all others. But this is a reality only for those concerned with acquiring and maintaining power. For everyone else, the failure to accept the true reality, that all people have at one time been migrants, that there are no original peoples, no supreme cultures and languages, and that we have no choice but to contend with the multitude of variations of "otherness" that surround and inhabit us all, is a very serious mistake, indeed.

That we are incapable of providing immigrant youth with education that truly responds to their needs is not surprising in a country that cannot accept its own fundamental hypocrisy. If we are to implement policies that promote multiculturalism, we cannot continue to use terms like integration. If we want educational integration to be about embracing diversity, we cannot implement programs that essentially segregate the Canadians from the non-Canadians and then expect there to be harmony within the student body.

The emphasis placed on language acquisition in educational integration programs is in itself indicative of a fundamental prejudice. The logic states that Canada has two official founding peoples, yet as we saw in the evolution of Canadian immigration policy, groups of immigrants remain unacknowledged for their contributions to the founding of Canada as a unified nation. Canada could have tens of official languages, yet this would require acknowledging the contributions of so-called immigrants, effectively shifting political power from two privileged groups (or one privileged group, white Anglophone, and one tokenized group, white Francophone) to dozens of deserving founding peoples.

Until we change (and ultimately dismantle) the fundamental power structures that reinforce the privilege of the few, any changes in policy or in practice in educational integration will be strictly cosmetic and reformist. The true change must be undergone in the larger society before there can be any real change within institutions, educational or otherwise.

Annotated Bibliography:

Allen, Dawn. "Who's in and who's out? Language and the integration of new

immigrant youth in Quebec." International Journal of Inclusive Education 10.2/3 (2006): 251-263. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 12 Oct. 2010. A critique of Quebec's educational integration policy and its definition of "integration". The article is based on findings from a study involving a representative group of immigrant youth enrolled in the Accueil program in Quebec.

Canada. Multiculturalism and Citizenship Canada. The Canadian Multiculturalism Act :

a guide for Canadians. Multiculturalism and Citizenship Canada, Ottawa, Ont, 1990. Self-explanatory.

Council of Ministers of Education, Canada; Canadian Commission for UNESCO.

"Report One: The Education Systems in Canada: Facing the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century." Development of Education: Reports for Canada. Toronto, 2008. Web. Oct 29, 2010.

Gregg, Allan. Multiculturalism: A twentieth-century dream becomes a twenty-first-

century conundrum. The Walrus. Toronto, Ontario, 2008. Web. 30 Nov 2010. Article that provides a useful timeline and overview of the evolution of immigration policy in Canada.

Khanlou, Nazilla, Jane G. Koh, and Catriona Mill. "Cultural Identity and Experiences of

Prejudice and Discrimination of Afghan and Iranian Immigrant Youth." International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction 6.4 (2008): 494-513. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 8 Nov. 2010. Provides insight into the experiences of visible-minority immigrant youth.

Li, Peter S.. Deconstructing Canada's Discourse of Immigrant Integration.

Edmonton, AB, Canada: Prairie Metropolis Centre, 2003. Web. 30 Nov, 2010. A very interesting critique of current discourse on immigration, particularly around terms such as integration. Reviews and critiques the various milieus in which this discourse is used.

Liying, Cheng, Don A. Klinger, and Zheng Ying. "The challenges of the Ontario

Secondary School Literacy Test for second language students." Language Testing 24.2 (2007): 185-208. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 6 Nov. 2010. A review of available ESL/ELD (English Language Development) resources available in Ontario and their impact on standardized language test results.

Mariekebw [Marieke Bivar-Wikhammer]. "Educational Integration or Cultural

Segregation? Examining Quebec's Accueil System." WordPress. WordPress, 19 Oct. 2010. Web. 9 Nov. 2010. A synthesis of two studies that raise questions about the effectiveness of Quebec's "Accueil" program.

McAndrew, Marie. "Ensuring Proper Competency in the Host Language: Contrasting

Formula and the Place of Heritage Languages." Teachers College Record 111.6 (2009): 1528-1554. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 6 Nov. 2010. Includes a comparative case study on language instruction in Quebec and Ontario and offers interesting insight into the interaction of second language instruction and students continued proficiency in heritage languages.

Quebec Ministries of Education, Relations with Citizens, and of Immigration. A School

for the Future: Educational Integration and Intercultural Education. Quebec, 1998. Web. 29 Oct, 2010. Policy statement from the ministries useful in ascertaining the current official discourse on educational integration.

Statistics Canada. Immigration in Canada: A Portrait of the Foreign-born Population,

2006 Census. 97-557-XIE. Ottawa, 2007. Web. 30 Nov, 2010. The most recent statistics available on the immigrant population.

Steinbach, Marilyn. "Quand je sors d'accueil: linguistic integration of immigrant

adolescents in Quebec secondary schools." Language, Culture & Curriculum 23.2 (2010): 95-107. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 12 Oct. 2010. A study focusing on the particular difficulties facing new immigrant students in rural Quebec.

Van Ngo, Hieu. "Patchwork, Sidelining and Marginalization: Services for Immigrant

Youth." Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 7: 1 (2009): 82 -100. Web. October 26, 2010. A detailed review of available services in the mainstream, those offered by settlement agencies, and those in place within schools.

Image source: http://radicalgraphics.org/collection/view_photo.php?set_albumName=School&id=dropouts

Leave a comment