The positive development of any given society is borne by its members and the contributions which they are allowed to make continue to enhance its progression. This statement can be true, if all members are willing participants and are allowed to share in the enrichment of their respective society. The level and manner towards this participation must be defined and determined by each individual/group. For every person acquires his/her own experiences and perspectives of the world, which are unique unto themselves. Permitting the inclusion of these perceptions would not only add to the social flavor of that populace, it would also increase the likelihood of its members reaching their human potential. To stifle this reality would limit the richness that that society could potentially reach. The depth of this progression could be capitalized on if the society was comprised of an array of ethnic groups. For each cultural community possesses its own distinct language, art, literature, food, religion, traditions and history.

The positive development of any given society is borne by its members and the contributions which they are allowed to make continue to enhance its progression. This statement can be true, if all members are willing participants and are allowed to share in the enrichment of their respective society. The level and manner towards this participation must be defined and determined by each individual/group. For every person acquires his/her own experiences and perspectives of the world, which are unique unto themselves. Permitting the inclusion of these perceptions would not only add to the social flavor of that populace, it would also increase the likelihood of its members reaching their human potential. To stifle this reality would limit the richness that that society could potentially reach. The depth of this progression could be capitalized on if the society was comprised of an array of ethnic groups. For each cultural community possesses its own distinct language, art, literature, food, religion, traditions and history.

The same is true for the Black community of Montreal, whose recorded history starts four hundred years ago with Mathieu DaCosta. DaCosta, a free Black African, who was the interpreter to the Native peoples for Samuel de Champlain and Pierre Dugua de Monts in 1608 and according to early documents he may have been present in the Port Royal Habitation in the Annapolis Basin in 1605. [1] Mathieu DaCosta was an experienced translator who had many interactions with the Europeans and spoke French, Portuguese and Dutch. It is assumed that his ability to communicate with the Aboriginal people stems from frequenting the Americas or learning "pidgin"a dialect used in the New World by the Basques of Spain, which the Natives understood.[2]

Approximately 100 years after Mathieu DaCosta landed in Montreal, King Louis XIV legalized slavery in New France in 1709. [3] According to historian, Marcel Trudeau, Montreal was home to 2077 slaves during its early formation. [4] One of the most notable slaves in Canadian history is Marie-Joseph Angélique. Marie-Joseph was a black slave born of Portuguese descent who was owned by Therese de Couagne and her husband, Francois Poulin de Francheville. [5] There are different reports about the reasons behind her intended escape from her master. One report states that she feared being sold by her master and the second report states that she and her White lover, Charles Thibault, intended to flee the city to be together. In any event, Angélique is recorded as having set fire to Couagne's home to cover her impending departure in the evening of April, 1734. As a result the fire destroyed a hospital and 45 homes on Saint-Paul Street. [6] Marie-Joseph was caught, imprisoned, tortured until she confessed to the crime and was found guilty in June of the same year. Her sentence was the death penalty, which took place after she had been paraded around town and her hand was amputated. After her hanging, her body was burned and her ashes thrown to the wind. [7]

JANUARY 1792 - THE BLACK LOYALIST EXODUS: Due to economic hardships and widespread discrimination 1200 Blacks leave Nova Scotia and sail across the Atlantic Ocean to settle in Sierra Leone. [8]

JULY 1796 - THE MAROONS LAND IN HALIFAX: Six hundred Maroon immigrants arrive in Nova Scotia from the community of escaped slaves from Jamaica. They had preserved their freedom and countered many attempts to be re-enslaved. [9]

Canada was the final destination for many fugitive slaves who either escaped with Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad or alone. Between 1815 and 1860 thousands of African-Americans arrived in Upper and Lower Canada seeking refuge. [10] Not all Blacks arrived in Canada as slaves during this period in time. For example, George Bonga, son to an African-American slave and an Ojibwe mother was a free Black man. He attended school in Montreal for an undisclosed time frame. Fluent in English, French and Ojibwe, Bonga was an excellent fur trader and interpreter in the Minnesota Territory. [11]

With the influx of fugitive slaves, immigrants from the West Indies and Blacks born in Canada, the cultural population of Canada was developing new hues. Despite the harsh winters and financial uncertainties, Blacks envisioned this country to hold more opportunities in terms of education, land ownership and a general sense of freedom. Even though racism was prevalent, it was an improvement to the living conditions experienced in the southern states of America.

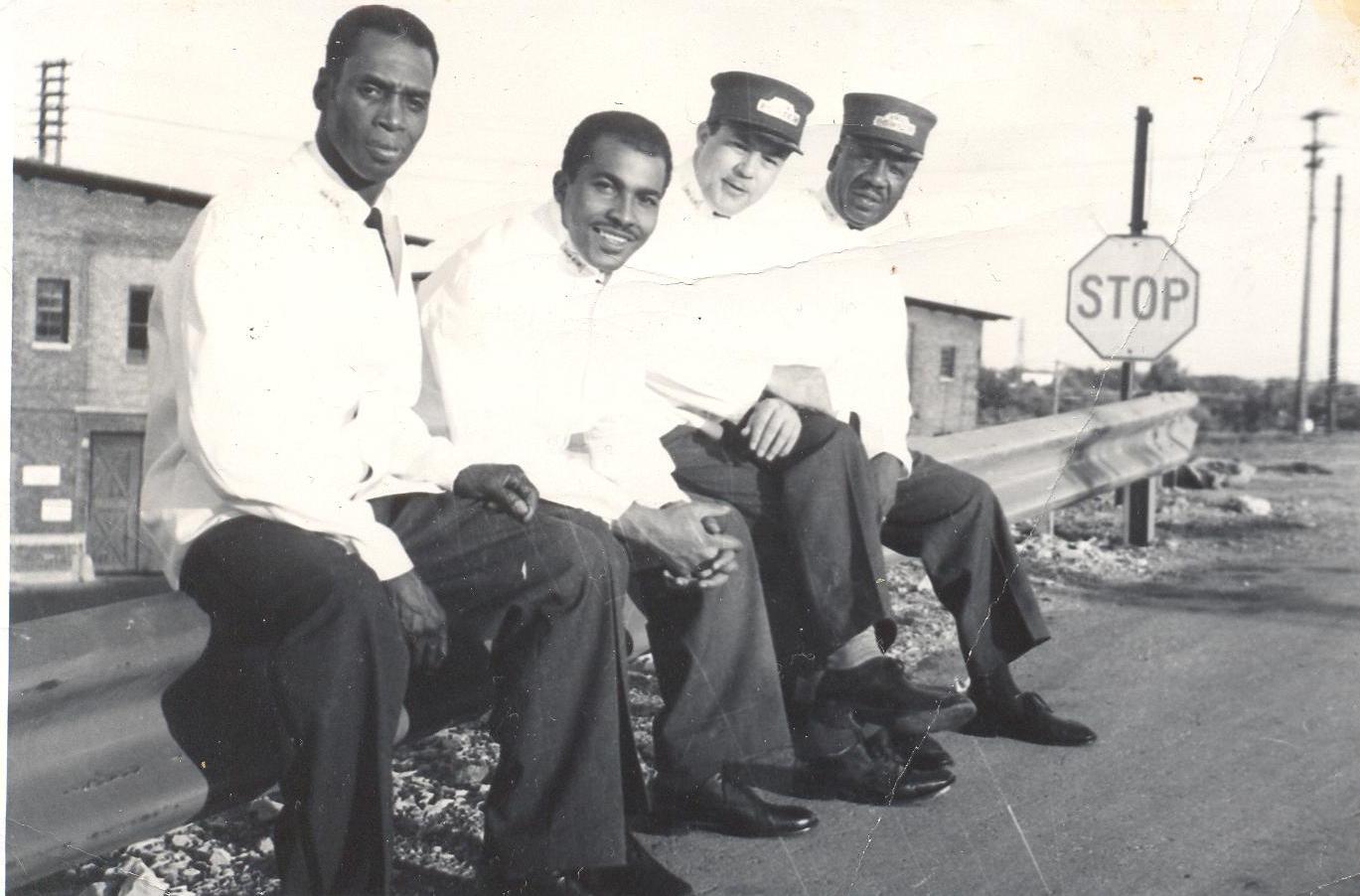

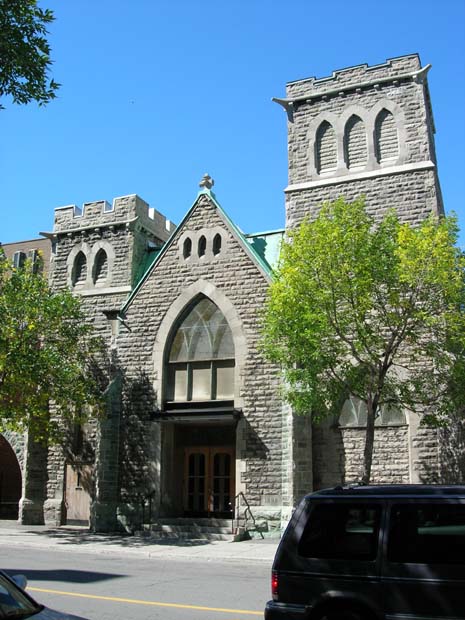

In the 1880s the Black community of Montreal began to concretize and embarked on a pathway towards "do for self."The Canadian Pacific Railway established its headquarters and training center in Montreal. In order to maintain minimal labor costs, the red caps, sleeping car porters and cooks positions were reserved for Black males, while the women tended to work as domestic servants. These jobs became the steady employment for young men of color regardless of their educational achievements. African Americans were recruited from the United States to fill these positions as well. Hence the population increased in the downtown areas. With a strong desire to look after their spiritual needs, develop a sense of unity within the community and counter the exclusionary reception received by the White congregations, a small group of porters decided to build their own church. The first organizational meeting was held July 1907 and with the sacrifices made by men and women, the congregation moved into the premises at 3007 Delisle, corner of Atwater in 1916. The Union United Church along with the Colored Women's Club of Montreal, a social club organized in 1900, started a clothing outlet for Black immigrants facing their first winter and provided food and shelter to the less fortunate. [13]

Most of the organizations that were started in the early 1900s, supported the church's philosophy of assisting those who were in need of help, promoting the active participation of all members and maintaining a close-knit bond. One of the organizations that sprouted up during this time was a chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, founded by Marcus Garvey, who had delivered an inspirational speech to the community. They were motivated by his message that the Black man should recognize his capabilities and talents and not to shy away from demanding his rights. This group also laid strong emphasis on the youth in order to provide them with self-confidence, a sense of belonging, an understanding of their history and social activities that would help them as they matured.[14]

After 1918, the West Indian population in Montreal increased hoping that they would be able to find employment in the skilled labour field, in which they excelled. To their dismay, the only vacancies were on the railroads. Some remained in the city, while others migrated to America. With this, the membership at the church increased. In 1925, Reverend Charles H. Este became the church's minister and the community's leader as they fought against the "Color Line" within employment, poor or discriminatory housing conditions and social issues. Reverend Este, as he was affectionately known, is also credited with being the co-founder of the Negro Community Center. The center initially started in the church basement (currently located on Coursol street), with the objective of increasing community awareness, removing barriers to unlawful hiring practices and facing any injustices that were inflicted upon the community members. The primary activities were directed towards the youth and included a gym and music sessions. During the depression, the church maintained its role as the backbone of the community and continued to provide for the needs of the people. Jobs were scarce as many were laid off from the railroads and Reverend Este ensured that the city provided sustenance to the forgotten community.[15]

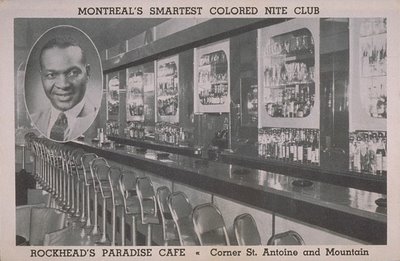

One of the other social activities that appeared in the early 1930s, was Rufus Rockhead's Paradise, a jazz club that opened on the corner of St-Antoine and Mountain. Born in Jamaica, Rockhead obtained a liquor license in his own fashion and his establishment gained the reputation for being one of the hottest spots in Montreal. His night club hosted the top jazz musicians from New York such as Eartha Kitt, Dizzy Gillepsie, Sarah Vaughn, Billie Holiday, Redd Foxx and Sammy Davis, Jr. to name a few and others, who would stop by to just to chat with the owner like Pearl Bailey and Louis Armstrong. [16]

Montreal is also home to some local musicians who have gained international acclaim with their extraordinary agility, these words are related to none other than Oliver Jones

and the late, great Oscar Peterson

In addition, the Black community also cherishes the memory of Dr. Charles Drew, an American clinician who was trained at McGill University and did his internships at Royal Victoria Hospital and the Montreal General Hospital. While studying at McGill he developed an interest in blood plasma and technology. He played a major role in the "collection of blood for the American armed forces."[17]

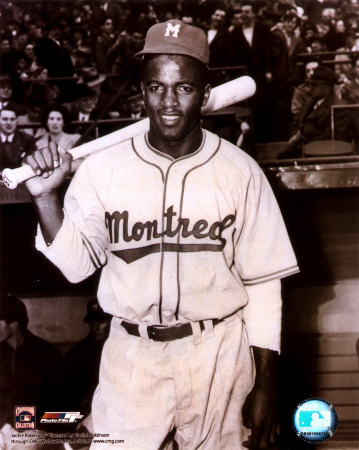

Jackie Robinson also deserves mention as one who brought international recognition to the Black community in Montreal when he played for the Montreal Royals in 1946 and for his role in breaking the color barrier in professional baseball.

Blacks continue to make contributions to the society at large, but those contributions are coming from a much more diverse Black population.

CURRENT SITUATION: The wave of Black immigrants continues to flow into Canada, but as of the 1960s, with improved economic and social conditions many people of color have moved from the downtown core of Little Burgundy to other sections of town, mainly Cote-Des-Neiges, N.D.G, Verdun, LaSalle and the West Island. In addition, the presence of the Haitian migrants arrived around the same time and they established themselves away from the English-speaking Blacks to establish a community in Montreal-North. By 1986 their numbers reached 38,000 from 17,000 in 1977. Although they cherished higher education, still 25% of Haitian immigrants were unemployed. Their median income was half that of the average Quebecois. This resulted in limited housing opportunities and they thus settled in Central, North and North-east sections of Montreal.

By the 1990s, 23.8% of Africans who migrated to Canada settled in Quebec, but in cities off the island of Montreal like Quebec City, Trois-Rivières and Gatineau. Africans are also highly educated, more than 80% had completed their university studies and 64% stated they were unemployed between one to five years. These statements came from the English-speaking Africans who were living in Montreal. Despite their geographical background, all Blacks have had and are still struggling with inadequate living conditions, youth unemployment, social acceptance and discrimination within the society.[18]

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE:

As history dictates, the presence of Blacks in Montreal has been accompanied by a strong work ethic, a desire to be a successful and contributing members of society and one which denounces the media stereotypes. Considering that the social improvements have not altered significantly since the mid-1960s, there is a potential for increased poverty and marginalization. With the given economic fluctuations in today's world, the Black community will have to investigate alternative means to gaining lawful employment. Which may require returning to school to further one's skills or being on the forefront of the latest technologies. The community may have to modify their fields of study to meet the diverse needs of the future and step outside of the normal course of educational pursuits.

In addition, community leaders may have to work with government agencies to develop school curriculums and before and after school programs to counter the potential issues related to poverty and youth unemployment. In conjunction with school programs, certain legislation may have to be enacted to increase access to blue and white collar jobs. Otherwise, the potential exists for youth-related crime levels to reach irreversible percentages. Which may result in escalating tensions between the police and the Black community.

As has been demonstrated their is a relunctance to engage the Black population in meaningful employment, which may be related to prejudiced or racist attitudes. These practices will only be eliminated if there is meaningful dialogue and cultural exchange between all members of society. There needs to be a concerted effort on the part of the educational institutions to incorporate inclusive historical readings and resources within the instructional materials. This may take a few generations to implement, but it will be worth the wait.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

[1] - The Canadian Library Association. The Mathieu DaCosta Challenge - Unity in Diversity. Historicas Educators Guide. <http://www.gnb.ca/0131/pdf/h/hw/MDCChallengeEducatorsGuide.pdf>

[2] - Historica Dominican Institute - Black History Canada <http://blackhistorycanada.ca/events.php?id=21>

[3] - ibid

[4] - Montreal Chronology. < http://ericsquire.com/docs/mtlchronology.htm>

[5] - http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=16544542

[6] - Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History: Torture and Truth: Angélique and the burning of Montréal. <http://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/angelique/accueil/indexen.html>

[7] - http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=16544542

[8] - Historica Dominican Institute - Black History Canada <http://blackhistorycanada.ca/events.php?id=21>

[9] - ibid.

[10] - ibid.

[11]- Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, Who was George Bonga? November / December 2010 edition. <http://files.dnr.state.mn.us/publications/volunteer/young_naturalists/george_bonga/george_bonga.pdf>

[12]- Some Missing Pages: The Black Community in the History of Quebec and Canada < http://www.learnquebec.ca/en/content/curriculum/social_sciences/features/missingpages/>

[13] - David C. Este. "The Black Church as a Social Welfare Institution: Union United Church and the Development of Montreal's Black Community, 1907-1940." Journal of Black Studies , Vol. 35, No. 1 (Sep., 2004), pp. 3-22. Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. <http://0-www.jstor.org.mercury.concordia.ca/stable/4129288>

[14] - Ibid.

[15] - Ibid

[16]- Some Missing Pages: The Black Community in the History of Quebec and Canada < http://www.learnquebec.ca/en/content/curriculum/social_sciences/features/missingpages/>

[17] - Ibid.

[18]- James L. Torczyner. D.S.W and Sharon Springer, M.A. The Evolution of the Black Community of Montreal: Change and Challenge. 2001 < http://www.mcgill.ca/mchrat/sites/mcgill.ca.mchrat/files/BlackDemographicStudy2001.PDF

PICTURES:

1) Mathieu DaCosta, Photo credit: http://blackhistorycanada.ca/events.php?id=21

2) Marie Joseph Angélique, Photo credit: http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=16544542

3) Photo credit: The Black Studies Centre, Montreal, Quebec

4) Black Porters, Photo credit: http://outerregion.hackinghistory.ca/the-walk/the-railroad-porter/

5) Union United Church, Photo Credit: http://www.imtl.org/montreal/image.php?id=463

6) UNIA Members. Photo Credit: Some Missing Pages: The Black Community in the History of Quebec and Canada

7) Rockhead's in the News, Photo credit: http://coolopolis.blogspot.ca/2009/03/name-that-businessman.html

8) Oliver Jones, Photo credit: http://www.514-billets.com/concert/oliver+jones

|

9) Oscar Peter - Photo Credit: |

©2011-2012 |

, http://aosfish.deviantart.com/art/Oscar-Peterson-192181264

10) Dr. Charles Drew, Photo Credit: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/Narrative/BG/p-nid/337

11) Jackie Robinson, Photo Credit: http://studenttrip.wordpress.com/2011/12/20/montreal-did-you-know-2/

Leave a comment