Although Aboriginals attended residential schools during the late 19th to mid-20th century, their pain and suffering are still evident today. The children were sexually, physically, psychologically, and spiritually abused. These emotional scars are still in effect, either through the attendees themselves, or through their families.To further stipulate, the abuse that the attendees received were passed down knowingly and unknowingly to their family members, especially their children. As the attendees were children themselves, they grew up in an environment where abuse was habitual and seemed normal. Therefore, when they had children themselves, they often imitated the habits they learned at school, consciously or unconsciously. This created discord amongst the communities where drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and sexual abuse are still active today. The main focus is that not enough action has been done to provide treatment and closure to the victims and their families.

BACKGROUND HISTORY

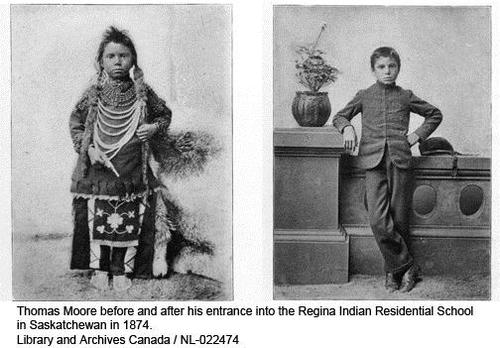

The first residential school opened around 1874, and they existed until the last one closed in 1996 (Corntassel 138). They were built because the government of Canada wanted to fix what was called the "Indian problem" (Llewellyn 256). After the war in 1812, the government did not need the Aboriginals anymore and a greater influx of British settlers forced the natives to live scattered amongst the settlements. This created disharmony between the two groups. Because the Aboriginals were financially tied with the government as "wards", the government thought it was best for everybody if they could assimilate the natives and at the same time get rid of the "Indian problem" and its costs (Llewellyn 256). Ted and Virginia Byfield write about the government's choice to hire priests and nuns: "The churches were asked to staff them because priests, ministers and nuns would dedicate their lives to the task for very little pay" (2-3). The government and the colonies deemed that it was a solution for an escalating problem and thus, the first school was opened during mid-1800. They hoped that by assimilating a large population of aboriginal children, they could adopt the 'white' ways of life and pass it on to others.

Since the government took total control over the schools, which they classified as "total institutions", it was the job of the institution to "re-socialize" the children by submitting them to any type of forced learning (Llewellyn 257). This type of assimilation involved "imposed conditions of disconnection, degradation, and powerlessness on the students" (Llewellyn 257). Therefore, abuse was generally encouraged so that the children learned faster. Many of them suffered sexual, physical, psychological, and spiritual abuse while being malnourished at the same time. They were punished and reprimanded when they spoke their ancestral language and many were not allowed to visit their siblings because they separated the sexes.

While not every student was abused at the school, the experience of being forcefully removed from their homes, families and communities by the government left emotional scars. Brenda Elias and fellow writers note that "many residential school children experienced a loss of culture, language, traditional values, family bonding, life and parenting skills, self-respect, and the respect for others. Their parents, in turn, lost their roles as caregivers, nurturers, teachers, and family decision-makers" (1561). Basically, the residential school shattered the bond between child and parent; between self and others. This continued on until the last residential school was closed in 1996. People may wonder if police were called to some of the schools where abuse was obviously going on. Some recall that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) aided in transporting children to the schools, while others remember that some officers helped stop a beating of a child during one school session (Narine 8). There is not enough written evidence to prove what exactly happened between the schools and the RCMP at the time.

THE CURRENT SITUATION

Although the residential schools have been closed for almost two decades, the grief and traumas that the survivors' endured are still alive because of the abuse they received and witnessed during their schooling. Amy Bombay, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman note: "Not surprisingly, as a result of these experiences, the capacity of [Indian residential school] survivors to socialize the next generation to cultural norms and practices, including parenting skills, was profoundly undermined" (368). They continue with: "In a national survey, First Nations adults reported that their parents' attendance at IRS negatively affected the quality of parenting they received as children" (369). In short, the attendees of residential schools adopted "inappropriate behavior patterns" towards themselves and others such as their surrounding families and future children (Bombay/Matheson/Anisman 369). Sylvia S. Barton, Harvey V. Thommasen, Bill Tallio, William Zhang and Alex C. Michalos note that most residential school survivors suffer from what is known as Residential School Syndrome (RSS), which avertedly almost resembles posttraumatic stress disorder. Features of Residential School Syndrome include:

- Recurrent intrusive memories

- Nightmares

- Occasional flashbacks

- Avoidance of anything that may be reminiscent of the residential school experience

- Relationship dysfunction

- Diminished interest and participation in cultural activities

- Sleep difficulties

- Anger management difficulties

- Tendency to abuse alcohol or sedative medication drugs

(MacMillan et al., 1996; Young, 1994)

What the list suggests is that survivors of residential schools have knowingly and unknowingly passed on the RSS onto their children by their behavior patterns. This has created generations of disharmonized aboriginal elders, adults, and children and little has been done to aid them.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE FUTURE

The Truth and Reconciliation Canada Commission of Canada (TRC) was introduced to help stop the cycle of depression and to help heal the survivors and their families (Corntassel 138).

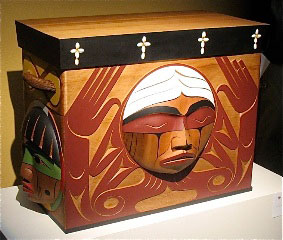

The TRC have set up events to specifically target survivors and help their healing process. In June 2010, the TRC gathered with survivors in Winnipeg to give them the chance to talk about their experiences and traumas. A Bentwood box with all the symbols of the Native people was erected to symbolize all of their pain (Narine 8). Back in July 2004, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation along with the TRC hosted workshops so that survivors could start their healing process (Carter 24). The government as well has given cheques to survivors as compensation of their distress by attending the schools.

In 2007, the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement came into effect, providing "Common Experience Payments" to former students at the rate of $10,000 for the first school year plus $3,000 for each additional year ("Indian Residential Schools"). In addition, survivors who suffered "sexual or serious physical abuses" are eligible to apply for additional funds through the Independent Assessment Process (Henderson & Wakeham 11).

Some may perceive this as easy money to the survivors, but one survivor Paul Daniels said: "The compensation I'm waiting for plays a very minor part in (my healing). I wish we would be treated the same as anyone else" (Narine 8). Indian Life Magazine reported that one residential school survivor, William Woodford, donated his 50 000 dollar compensation cheque to Siloam Mission, a shelter that takes care of Canada's Aboriginal peoples (1).

Apart from the monetary allocation given from the government, a public apology from Prime Minister Steven Harper (which received mixed reactions from the victims), and annual healing workshop events held by the TRC, nothing else has been done to help provide complete closure for the residential school attendees. Without closure, the cycle of interfamilial abuse will continue.

Works Cited

Llewellyn, Jennifer J. University of Toronto Law Journal; Summer2002, Vol. 52 Issue 3, p253, 48p

Barton, Sylvia S. Thommasen, Harvey V. Tallio, Bill. Michalos, Alex C. Zhang, William. Social Indicators Research; Aug2005, Vol. 73 Issue 2, p295-312, 18p

Corntassel, Jeff. English Studies in Canada; Spring2009, Vol. 35 Issue 1, p137-159, 23p

Indian Life; Mar/Apr2009, Vol. 29 Issue 5, p3-3, 1/3p

Carter, Carl. Windspeaker; Aug2004, Vol. 22 Issue 5, p24-24, 1p

Narine, Shari. Windspeaker; Aug2010, Vol. 28 Issue 5, p8-8, 2/3p, 1 Black and White Photograph

Bombay, Amy. Matheson, Kimberly. Anisman, Hymie. Transcultural Psychiatry; Sep2011, Vol. 48 Issue 4, p367-391, 25p

Byfield, Ted & Virginia. Alberta Report / Newsmagazine; 11/04/96, Vol. 23 Issue 47, p40, 2/3p, 1 Black and White Photograph

Henderson, Jennifer. Wakeham, Pauline. English Studies in Canada; Spring2009, Vol. 35 Issue 1, p1-26, 26p

Narine, Shari. Windspeaker; Dec2011, Vol. 29 Issue 9, p8-8, 1/3p

Residential School Girl Photo: http://www.turtleisland.org/discussion/viewtopic.php?f=4&t=3202

Thomas Moore Photo: http://bethblogever.blogspot.ca/2012/04/truth-reconcilation-listening-to.html

Bentwood Box Photo: http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/index.php?p=42

Leave a comment