Image Source: Flicker--caribb

What do you believe is being covered by the red tape on this sign? If you guessed the English translation of the French word 'arret'--the word 'stop'--then you guessed correctly. While this image implies that there is no need for the English language on signs of public administration in Quebec, this implication is false insofar as Quebec is a Francophone province in an Anglophone country and, furthermore, insofar as there is a substantial English minority in Quebec. Although you would not be able to determine these facts by examining the signs of public administration, such as this stop sign, as they are exclusively in French, you may be able to determine that Quebec is culturally diverse by examining the advertisements found in this province. However, your examination should lead you to pose the following questions: why are all advertisements in Quebec either exclusively or predominately French and, in the latter case, why is the secondary language displayed substantially smaller than the French language? The response to these questions is that advertisements in Quebec are merely conforming to the regulations of Bill 101--the Charter of the French Language.

While Bill 101 has more than 200 provisions in a sum of six titles--or sections--the simple description of the provisions found in its first and second titles discloses its oppressive nature towards the English language. The first title--Status of the French Language--defines French as "the official language of Quebec" and stipulates that advertisements in Quebec must be exclusively or predominantly in French (Bill 101). Although the second title--Linguistic Officialization, Toponymy and Francization--has been mostly repealed, the chapter on the francization of enterprises, which oblige business in Quebec to operate in French, remains prevalent. While I concede that it is the Charter of the French Language, and is therefore biased towards French, Bill 101 oppresses the English language by imposing regulations on English businesses, making it difficult for them to thrive in Quebec and discouraging new English businesses from investing in our province.

The road to Bill 101

Image Source: Flicker--Dino ahmad ali

The road to Bill 101 began in "the fall of 1969" when the National Assembly of Quebec assented to Bill 63--Loi pour la langue française au Quebec (Bélanger). Jean-Jacques Bertrand, heading the Union National government, agreed to pass Bill 63 into legislation in an effort to apease the Francophone demand "for a more French Quebec" and the Anglophone demand for "the recognition of minority rights" (Bélanger). Having been assented to, however, the Bill failed to appease the Francophone community, as it threatened the "position of dominance" of the French language in Quebec by guaranteeing that parents could choose "the language of instruction for their children" and by accelerating the assimilation of Allophones into Anglophone communities (Bélanger). In effect, the Gendron Commission was established "to study the status of the French language"; the study concluded with the recommendation of Bill 22 (Bélanger).

Bill 22--Loi sur la langue officielle--was passed into legislation "by the National Assembly of Quebec in 1974" (Bélanger). Robert Bourassa, heading the Liberal government, assented to Bill 22 in an effort to resolve the problems caused by Bill 63; Bourassa sought to "reconcile the promotion of the French language" with the "protection of minority rights" (Bélanger). Bill 22 decreed French to be "the official language" of Quebec and established the "Régie de la langue française," whose function it was to ensure "the application of the Bill" (Bélanger). Bill 22 required, among other things, that advertisements had to be "primarily in French in Quebec" and that enterprises had to obtain "a certificate of francization" in order to continue operating, which could only be obtained when a business demonstrated that it "could function (...) and address its employees in French" (Bélanger).

Both the English and French opposed Bill 22. While the French argued that Bill 22 "did not go far enough," the English contended that "it went much too far" (Bélanger). Consequently, the English refused to vote for Bourassa's Liberal party in the upcoming election, contributing to "the election of the Parti Québécois" in November of 1976 (Bélanger). Soon after the election, in 1977, René Levesque, heading the Parti Québécois, passed Bill 101--Charte de la langue française--into legislation (Bélanger).

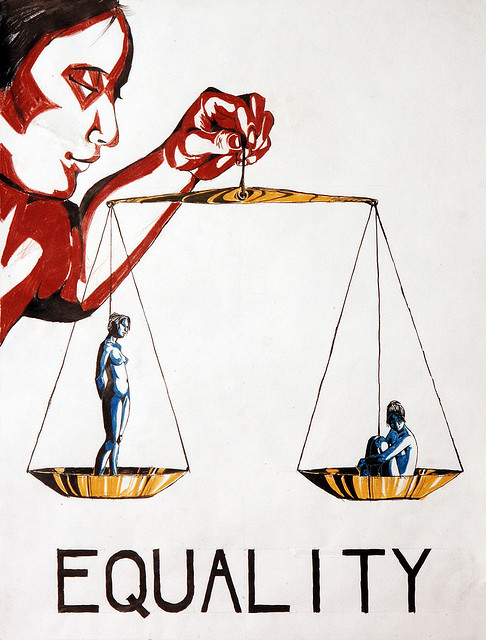

Bill 101: The Oppression

In the Preamble of the Charter of the French Language, the third assertion states that the National Assembly intended to promote the French language "in a spirit of fairness and open-mindedness, respectful of the institutions of the English-speaking community of Quebec"; however, a close analysis of the provisions of Bill 101 suggest that the National Assembly, in passing this Bill into legislation, neither assumed a spirit of fairness nor was respectful of English-speaking institutions (Bill 101).

Image Source: Flicker--Saxarocks

Bill 101: Advertisment Laws

Although the Preamble does suggest that the Charter will be open-minded, the Charter's spirit of oppressiveness begins to emanate from the first title--Status of the French Language. The first chapter of this title--which evidently has only one provision--decrees that "French is the official language of Quebec" (Bill 101). Note that it does not say that French is one of the official languages of Quebec; rather, it implies that French is the only official language of Quebec. Given that Quebec did at that time have a substantial English minority, a minority which its government was attempting to appease, this stipulation appears to be an act of intentional oppression.

Six chapters later, in Chapter VII--The language of Commerce and Business--of the first title, provision 58 declares that public "signs and posters and commercial advertising must be in French"; however, they "may also be both in French and in another language provided that French is markedly predominant" (Bill 101). The French language is markedly predominant, according to the Charter, when it "has a much greater visual impact than the text in the other language," and it continues to stipulate what is defined as having 'a much greater visual impact' (Regulations defining). If the texts both appear on a single sign, then the French text has a much greater visual impact if (1) "the space allotted to the text in French is at least twice as large as the space allotted to the text in the other language"; if (2) "the characters used in the text in French are at least twice as large as those used in the text in the other language; and if (3) "the other characteristics of the sign or poster do not have the effect of reducing the visual impact of the text in French" (Regulations defining).

Similar absurdities apply when the texts appear on separate signs of equal size--the signs with the text in French must be "at least twice as numerous"--and when the text appear on separate signs of different sizes--the signs with the text in French must be "at least twice as large" (Regulations defining). Do you believe that these regulations emanate a spirit of fairness and open-mindedness or a spirit of oppression? I am inclined to believe that the latter case is true.

These regulations on advertisement allow the "Office Quebecois de la Langue Franҫaise" (OQLF) to persecute enterprises for having a language in their advertisement that is equally predominant as the French language.They permit inspectors of the OQLF to approach signs with a ruler, measure them for minute discrepancies, and fine individuals who violate the law by a few centimeters--literally. Despite what some may believe, measuring for minute discrepancies and searching for characteristics that reduce the visual impact of the text in French are common occurrences. In fact, a personal acquaintance has had the OQLF accuse him of having on a sign in front of his enterprise text in English that reduces the visual impact of the text in the French, when the text in French did conform to the first two requirements of provision 58.

Furthermore, these regulation allow the OQLF to persecute enterprises for displaying words without making their French translations markedly predominant. In a recent case, Massimo Lecas--owner of the Italian restaurant Buonanotte--was instructed to translate his menu because it contained "too much Italian" (Is 'pasta'). The menu contained the words "botiglia, pasta, and antipasto" without a markedly predominant French translation (Is 'pasta'). In another case, Toby Lyle--owner of Brit & Chips, a fish and chips restaurant--was instructed by the OQLF to make a number of alterations, which included adding "the word 'restaurant' predominantly" above the entrance of his enterprise, changing "the signs on the washrooms" and reducing "the size of the English lettering" on a take-out sign (Is 'pasta'). While Lyle agreed to conform to these demands, he refused both to change the name of the "restaurant's main dish to "poisson frit et frites" and to remove the advertisement "'fish and chips' from the window," as he believed that making such alterations would "push customers away" (Is 'pasta').

Image Source: Flicker--Cloudywind

The advertisement regulations of Bill 101 evidently oppress the English language by imposing regulation on English enterprises and, furthermore, discourage new English businesses from investing in Quebec. These regulations allow English businesses--and businesses of other languages--to be persecuted for the smallest discrepancies in their advertisements. Moreover, the interpretation of the criteria 'having the effect of reducing the visual impact' remains open, entailing that whether advertisements violate the Bill's regulations depend upon the discretion of OQLF investigators--and possibly their mood. On the other hand, these regulations discourage new English businesses from investing in Quebec as doing so entails that their advertisement costs necessarily double and that they are open to scrutiny from OQLF investigators. Furthermore, these regulations discredit the position of the French in Quebec insofar as they come to appear as oppressing nationalists. While some level of nationalism is required to preserve the French language in Quebec, that level of nationalism does not require oppression; if advertisement regulations required the French language to appear equally predominant as the other language being displayed, then that position would not only be attainable, but acceptable and accepted by the province at large.

Bill 101: Francization of Enterprises

While the regulations on advertisement dramatically increase the cost of advertising, the regulations concerning the francization of enterprises overwhelm medium sized English businesses. The fifth chapter--Francization of Enterprises--of the second title--Linguistic Officialization, Toponymy and Francization--is concerned with the measures that enterprises in Quebec must satisfy if they wish to obtain "a francization certificate" from the Office Québécois de la Langue Française (Bill 101).

In order for an enterprise "employing 100 or more persons" to obtain a francization certificate, according to provision 136, the enterprise must establish "a francization committee composed of six or more persons" whose task it is to "devise a francization program and supervise its implementation" (Bill 101). The purpose of the francization program, according to provision 141, is to "generalize the use of French at all levels of the enterprise" and to ensure that the Charter's condition regarding the use of the French language have been satisfied (Bill 101). According to the Charter, an enterprise must achieve the following objectives through a francization program in order for a certificate of francization to be issued; the enterprise must

- (1) hire management that has "knowledge of the official language";

- (2) increase "the number of persons having a good knowledge of the French language" at each level of the enterprise;

- (3) establish "French as the language of work and (...) internal communications";

- (4) employ "French in the working documents of the enterprise";

- (5) impose "the use of French in communications with the civil administration, clients, suppliers, the public and shareholders"

- (6) insist on "the use of French terminology",

- (7) require "the use of French in public signs and posters and commercial advertising"

- (8) develop "appropriate policies for hiring, promotion and transfer"

- (9) and it must promote "the use of French in information technologies"

(Bill 101).

In order for an enterprise employing "50 persons or more for a period of six months" to get a certificate of francization, the enterprise must first obtain "a certificate of registration," as stipulated by provision 139 (Bill 101). To obtain a certificate of registration, the enterprise must provide the OQLF with "the number of persons it employs (...) with general information on its legal status and its functional structure and on the nature of its activities" (Bill 101). Having provided the OQLF with the required information, within six months, the enterprise will receive a certificate of registration and, within six months of its reception, will have to transmit to the OQLF "an analysis of its linguistic situation" (Bill 101).

If the OQLF finds in the enterprise's analysis that the use of French is sufficiently generalized at each level of its operation, according to provision 140, it will issue the enterprise a certificate of francization (Bill 101). However, if the OQLF finds that the use of French is not sufficiently generalized, then it will direct the enterprise to develop and "adopt a francization program," which must be submitted to, and subsequently approved by, the OQLF (Bill 101). Furthermore, the OQLF may "order the establishment of a francization committee of four to six members" (Bill 101).

In relation to enterprises employing 50 to 100 persons or more, once the OLQF approves the francization program, it issues the enterprise "an attestation of implementation" (Bill 101). However, according to provision 143, the enterprise will be required to submit a report to the OQLF on the program's implementation "every 12 months in the case of an enterprise employing 100 or more persons" and "every 24 months in the case of an enterprise employing fewer than 100 persons" (Bill 101). Once it is satisfied with the implementation of the francization program, according to provision 145, the OQLF will issue the enterprise a certificate of francization (Bill 101). Having recieved the francization certificate, provision 146 stipulates that the enterprise is required to continue ensuring "that the use of French remains generalized" (Bill 101). If the enterprise fails to uphold the obligations imposed by the Charter, however, the OQLF maintinas the authority to refuse, suspend or cancel either the attestation of implementation or certificate of francization, according to provision 147 (Bill 101).

Finally, according to provision 151 of the Charter, a business "employing less than 50 persons," upon the decision of the OQLF, may be required to "analyze its language situation and to prepare and implement a francization program" (Bill 101). At which point, that enterprise would be required to satisfy the objectives of a francization program, obtain a certificate of registration and attestation of implementation, and a certificate of francization (Bill 101).

The regulation on advertisement and the francization of enterprises clearly promote the French language, but do these provisions do so "in a spirit of fairness and open-mindedness, respectful of the institutions of the English-speaking community of Quebec"? (Bill 101). I think not. The Charter may be a charter concerned only with the French language, but that does not entail that it needs to oppress the language of the minority in this province. Yes, French is the official language of Quebec, but the English language has also been present in Quebec since time immemorial, as the road to Bill 101 indicates. Yes, French should be on each and every advertisement, but not in the manner required by the Charter; there is no need to make the French language appear markedly predominant, as its presence can be ensured by legislating that it be of equal predominance.

On the other hand, the measures concerned with the francization of enterprises are evidently directed at oppressing the English language through the imposition of regulations on English businesses in Quebec. The francization measures oppress the English language by imposing French as the language of operation on all enterprises and by making the attainment of a certificate of registration, an attestation of implementation and a certificate of francization necessary requirements to operate in Quebec. In addition, these measures oppress the English language by requiring that enterprises recurrently establish that they continue to satisfy the provision articulated in the Charter. Furthermore, these measures place an unnecessary burden on English businesses insofar as their success is dependent upon being able to communicate with their clientele in a province with a French majority.

Finally, the francization measures discourage new English enterprises from investing in Quebec insofar as its neighbouring province has more agreeable regulations and substantially less taxation. In essence, Bill 101 was not developed "in a spirit of fairness and open-mindedness, respectful of the institutions of the English-speaking community of Quebec," but in a spirit of oppression towards the English language and English businesses (Bill 101).

Works Cited

Belanger, Claude. The Language Laws of Quebec. 23rd August 2000. 17th March 2013 <http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/readings/langlaws.htm>.

Bill 101: Charter of the French Language. 1st April 2013. 17th March 2013 <http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=2&file=/C_11/C11_A.html>.

"Is 'pasta' French enough for Quebec?" 20th February 2013. CBC News. 14th April 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2013/02/20/montreal-language-pasta-translation.html>.

Regulation defining the scope of the expression "markedly predominant" for the purposes of the Charter of the French language. 1st November 2012. 28 November 2021 <http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=3&file=/C_11/C11R11_A.HTM>.

Protest rally. Against the charter. Sunday. 2pm. Place Jacques Cartier near metro champs du mars. Let your voice be heard. Peacefully!