Image Source: Flicker--scottmontreal

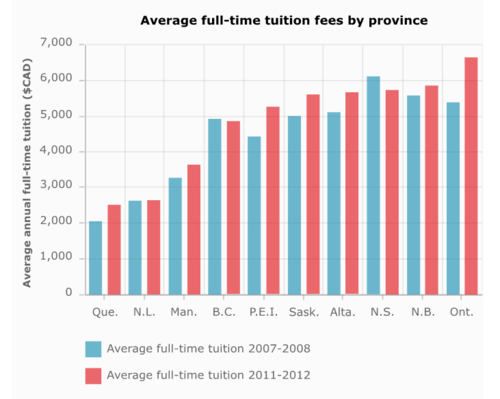

On March 18th, 2011, Raymond Bachand, Quebec's Minister of Finance, announced that Quebec intended to raise post-secondary tuition fees in September of 2012. Quebec's intention was to increase "tuition by $325" per year over a period of five years (Canadian Press). The total increase would "amount to an additional $1,625," an increase of nearly 75 percent, boosting annual tuition in Quebec "to $3,793 in 2017" (Canadian Press; Tuition hike).

Considering that tuition rates in Quebec have essentially remained unchanged over the past 40 years, the proposed increase in tuition is not extensive (Quebec students). The average annual tuition rate in Canada is $5,600 and, even after the proposed increase, Quebec would remain the province with the lowest annual tuition rate in the country (Tuition hike). Furthermore, Quebec taxpayers assume the larger part of tuition, as student pay "only 17 per cent of the total cost" of their post-secondary education (Massive student).

Image Source: CBC News

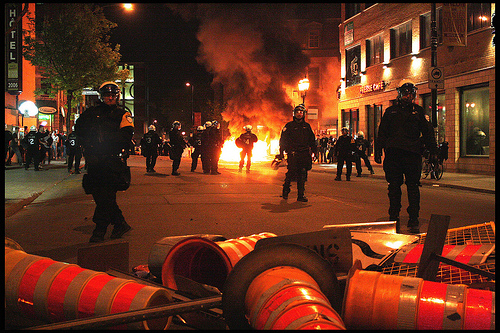

Despite these facts, according to some students in Quebec, the proposed increase in tuition would "limit access to higher education" and "result in crippling debt levels" (Tuition hike). Accordingly, these students boycotted educational institutions and protested in the streets; they disturbed classes, damaged property, disrupted society and disregarded injunctions. In response to the student protest, the provincial government of Quebec resorted to emergency legislation and assented to Bill 78, which has been declared by some as overly harsh and evidently unconstitutional.

Image Source: Flicker--Tina Malihot-Roberge

Student Activity in Montreal

Five months after Quebec's announcement, in August 2011, students formally began campaigning against the proposed increase in tuition, but it wasn't until November that students truly became active (Canadian Press). On November 10th 2011, over "20,000 students marched" to the Montreal office of Premier Jean Charest, but the march was only a small "part of a larger two-day strike being staged by an estimated 200,000 students across the province" (Quebec students). While the day's protests were largely peaceful, early in the morning, a group of students "blocked entrances at Dawson College in downtown Montreal," forcing Dawson to cancel its classes for the day (Quebec students). The activity at Dawson College crossed a line by preventing other student from attending classes; however, the activity that followed in February, March, April and May of 2012 went far beyond civil protest.

Student Activity: February

Three months after the incident at Dawson College, on February 13th 2012, the student protest became official with the first student associations "voting in favour of a walkout" (Canadian Press). However, some students felt that boycotting educational institutions wasn't going far enough so, on February 17th, these students "vandalized the Cégep Vieux-Montréal" (37 arrested). The assailants "entered the building, overturned furniture and set off fire extinguishers" before being arrested (37 arrested).

Image Source: Flicker--Thien V

Subsequently, on February 23rd 2012, student protesters occupied the Jacques Cartier Bridge in Montreal, one of the few arteries leading to the South Shore (Canadian Press; Montreal bridge). After directing the protestors to leave the bridge, a direction which the students failed to heed, the police used pepper spray to disperse the "thousands of student protesters who had shut down the structure for about 20 minutes (...) at the peak of rush hour" (Montreal bridge). These acts of disobedience, which marked the beginning of several months of unrest, had gone beyond civil protest to become social disruption and the students only became more aggressive in the months that followed.

Student Activity: March

On March 20th 2012, student protestors "blocked access to the Champlain Bridge" for approximately one hour, seriously delaying traffic onto the island from its South Shore (Students protesters). In response, the police rushed to the scene, loaded the protestors into two buses, escorted them "to a police station in Candiac, Quebec," and fined each protester "close to $500" for violating a provision of the Highway Safety Act (Students protesters). Something interesting to note is that the fine incurred for this act of disruption ($500) was greater than the proposed increase for the following year ($325).

Two days later, on March 22nd 2012, the students organized a "massive, peaceful protest" in which "more than 100,000" students demonstrated (Canadian Press). The demonstration is said to have been over a kilometer in length. Moreover, on the day of the protest, the student group referred to as C.L.A.S.S.E (Coalition large de l'Association pour une solidarité syndicale) "posted on its Twitter page" that subsequent student action would intentionally "disrupt the economy," if the government didn't retract the proposed increase in tuition (Massive student). To make good on that promise, on March 27th 2012, student protestors blocked access to the Liquor Board offices of Quebec (Canadian Press).

Image Source: Flicker--Flavie H.

Student Activity: April

Having disturbed classes, agitated society and disrupted the economy, the students became desperate because their tactics were failing--Quebec's government refused to budge on the proposed increase; accordingly, the students decided to take their protest one step further, beyond disruption into the realm of criminal activity.

On April 16th 2012, student protesters threw "bags of bricks" on to the tracks of three metro lines and "pulled the emergency brakes at five different stations," seriously delaying metro services and overwhelming public transit (Montreal mayor).

During the night of April 16th, student protesters vandalized the "offices of four Quebec cabinet ministers" (Canadian Press). The protesters "left windows damaged and buildings defaced" (Charest calls). Police found bottles, which they believed "to be incendiary devices," on the inside of smashed windows; however, none of the devices ignited and no injuries were reported (Charest calls). By the end of April, the police contend that there had been approximately "160 protest over 72 days" in Montreal alone (Canadian Press).

Image Source: Flicker--Alexandre Guédon

In an attempt to resolve the protest, on April 27th 2012, Quebec's provincial government offered students a revised proposal. The revised proposal offered a "slightly slower phase-in period" for the proposed increase in tuition and "more generous loans and bursaries" (Canadian Press). In addition, the revised proposal offered to index future increases in tuition to inflation (Canadian Press). While the protesting students conceded that the offer was reasonable, they argued that it ultimately wouldn't "save students money" (Quebec offers).

Student Activity: May

Having rejected Quebec's revised proposal, the protesting students continued with their criminal tactics. On May 10th 2012, student protesters paralyzed Montreal's metro system with "a series of smoke bombs," sending Montreal's public transit services "into chaos at the peak of rush hour" (Montreal mayor). According to police, "three smoke bombs were detonated on three metro lines" causing "a total shutdown" of the metro system (Montreal mayor). The affected stations were evacuated, thousands were stranded and the metro was jam-packed for many hours after reopening (Montreal mayor).

The final event leading to the emergency legislation occurred on May 16th, 2012, at "the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM)" (Masked student). Students at UQAM were issued "a court injunction" so that they could resume classes, but "hundreds of protesters" stormed UQAM's downtown buildings on the day classes were set to resume (Masked student). The protesters, "carrying a list of scheduled classes," invaded UQAM's buildings, "blowing whistles and banging on drums" as they searched for active classes (Masked student).

Image Source: Flicker--Alexandre Guédon

While the student demonstrations in April and May were greater than I have described, I have only outlined the most disruptive and criminal of their demonstrations in an effort to illustrate the activities legitimizing the harshness of Bill 78. Conversely, while some of the incidents in April and May cannot be definitively attributed to student protesters, the attacks ceased when the proposed increase in tuition was retracted, which only occurred after a provincial election that replaced the standing government.

Bill 78

In response to the social disruption and criminal activity of the protesting students, on May 18th 2012, Quebec's provincial government resorted to emergency legislation and, in a 68-48 vote, Quebec's National Assembly assented to Bill 78-- An Act to enable students to receive instruction from the post secondary institutions they attend (Quebec adopts; Bill 78). As its explanatory notes indicate, Bill 78 had three principal objectives: to suspended the academic terms of institutions with interrupted classes; to ensure "the continuity of instructional services" for institutions without interrupted classes; and to establish "provision to maintain peace, order and public security" (Bill 78 p2). Furthermore, Bill 78 instituted "penal measures to ensure enforcement of law" if any of its provisions were violated (Bill 78 p2). Once Bill 78 was passed, it suspended the semesters of "11 universities and 14 CEGEPs across Quebec"; it imposed "steep fines for anyone who tried blocking access to a school"; and it established "strict regulations governing demonstrations" (Emergency Quebec; Quebec adopts).

Bill 78: Division II

Of its 37 measures, the second division--Continuity of Instructional Services--contained 14 provisions; evidently, as its name indicates, this was the Bill's primary objective. This division addressed the suspension of academic terms, the continuity of instructional services and the right of access to an education.

The second provision of Bill 78 suspended the "2012 winter term and, in universities, the 2012 summer term" for institutions with classes that remained "interrupted on 18 May 2012" (Bill 78 p4). Disregarding the few exceptions, furthermore, this provision contended that institutions with suspended semesters must resume classes "not later than 7:00 a.m. on 17 August 2021" (Bill 78 p4). The third provision declared that every educational institution, including those individuals under its service, "must employ appropriate means to ensure" the continuity of instructional services, with the obligation imposed by this provision applying to "the applicable resumption date" of the suspended classes and "as of 7:00 a.m. on 19 May 2021" in each other case (Bill 78 p4).

Image Source: Flicker--heicktopiertz.com

The tenth provision of Bill 78 decreed that all employees of educational institutions "must, as of 7:00 a.m. on 19 May 2012, report for work according to their normal work schedule," while the eleventh provision added that such employees must "perform all duties attached to their respective functions (...) without any stoppage, slowdown, reduction or degradation of their normal activities" (Bill 78 p6). In other words, these provision obliged educational instructors of institutions without suspended semesters to resume their classes without delay and without a reduction in pace. However, according to provision twelve, provisions ten and eleven did "not prevent an association of employees from declaring a strike in accordance with the Labour Code," but did prevent such individuals from being involved in or organizing any activity that violated provisions ten or eleven (Bill 78 p6).

Provision 13 declared that "no one may, by an act or omission, deny students their right to receive instruction from the institution they attend or prevent or impede the resumption or maintenance of an institution's instructional services or the performance by employees of work related to such services, or directly or indirectly contribute to slowing down, degrading or delaying the resumption or maintenance of such services or the performance of such work" (Bill 78 p6). In English, as opposed to legalese, this provision entailed that, by an action or lack of an action, it was illegal; first, to deny a student access to an education; second, to prevent instruction from being provided or resumed; and third, to delay or slow down the resumption of educational services.

Finally, provision 14 decreed that "no one may, by an act or omission, deny a person access to a place if the person has the right or a duty to be there in order to obtain services from or perform functions for an institution" and, furthermore, that "any form of gathering that could result in denying such access is prohibited inside any building where instructional services are delivered by an institution, on the grounds of such a building or within 50 meters from the outer limits of such grounds" (Bill 78 p6). This entails that protestors could not prevent students or school officials from entering educational institutions and, furthermore, that demonstrations could not take place within 50 meters of school grounds; thus, demonstrations such as the ones that took place at Dawson College on November 10th 2011, and at UQAM on May 16th 2012, among other events, were declared illegal by this provision.

Bill 78: Division III & V

The third division of Bill 78--Provisions to Maintain Peace, Order and Public Security--was concerned with demonstrations in particular and has been criticized for infringing on the constitutional right of free association (Bill 78 p7). Provision 16 decreed that "the organizer of a demonstration involving 50 people or more to take place in a venue accessible to the public must, not less than eight hours before the beginning of the demonstration, provide the following information in writing to the police force serving the territory where the demonstration is to take place: (1) the date, time, duration and venue of the demonstration as well as its route, if applicable; and (2) the means of transportation to be used for those purposes" (Bill78 p7). Furthermore, according to this provision, if the police believed that "the planned venue or route" posed "serious risk for public security," then the police could, "before the demonstration, require a change of venue or route as to maintain peace, order and public security" (Bill78 p7). If the police came to have this belief, then the organizer of the demonstration was obligated to "submit the new venue or route to the police force within the agreed time limit and inform the participants" (Bill78 p7). A caveat, Los Angeles requires "far more than eight hours' notice--up to 40 days (...) in order to hold a protest," which makes this provision of Bill 78 appear relatively tame (Massive Montreal). In response to this provision, the protesting students submitted the following as a planned route for a demonstration.

Image source--businessinsider.com

The fifth division--Penal Provisions--was concerned with the imposition of fines for those found to have violated a provision of this Bill and it has been criticized for being overly harsh. According to provision 26, an individual who violated any of the provisions mentioned in this article was "liable, for each day or part of a day (...), to a fine of $1,000 to $5000" (Bill 78 p9). However, the fine increased to "$7,000 to $35,000" if the violation was committed "by (...) a representative (...) of a student association (...) or by a natural person who is the organizer of a demonstration" and it increased to "$25,000 to $125,000" if the violation was committed "by a student association (...) or a group that is the organizer of a demonstration" (Bill 78 p9). Furthermore, these fines "doubled for a second or subsequent offence" (Bill 78 p9).

Interview:

Image Source: Flicker--the|G|™

Some individuals contended that Bill 78 was unnecessarily harsh and, moreover, in violation of constitutional rights. These individuals asserted that the restriction preventing protestors from demonstrating within 50 meters of school grounds in addition to the requirement of prior notice for demonstrations involving more than 50 people violated the constitutional freedom of association. Furthermore, they contended that the steep fines imposed on the Bill's violators were overly harsh. In light of the disruption, disregard and destruction caused by the students, however, can this truly be said to be the case? I took this question to a citizen of Quebec who has two children, both of whom are students, and who once practiced law; this is what she had to say:

Question:

What qualifies you to be an authority on Bill 78?

Anonymous:

I am a mother of two children whom both attended Canadian Universities in different provinces. My son is currently studying at Concordia University's John Molson School of Business in Montreal and my daughter has recently finished her degree at Saint Francis Xavier's University in Nova Scotia. I have helped my kids pay for their tuition and the difference in cost is unbelievable; it is nearly twice the cost to attend University outside Quebec. On the other hand, I once practiced law, although it has been many years since I've practiced and my practice was brief. Despite my legal training being moderately out-of-date, I retain a relatively good understanding of the law. Finally, I am a Quebec citizen who experienced the civil unrest that resulted from the proposed tuition hike. I believe that these three facts qualify me to discuss Bill 78, although I am not sure whether they qualify me to be an authority on the issue.

Question:

When Bill 78 was passed on May 18th, 2012, the semesters of many educational intuitions with protesting students were suspended by the second provision of the Bill; should Quebec's provincial government have the authority to suspend the semester of these institutions?

Anonymous:

I would like respond to this question in two parts; first, I would like to address your question--whether the government should have the authority to suspend the semesters; and second, I would like to address the question whether or not they should have suspended the semesters.

I think that--yes--the government should have the authority to suspend the semesters of public schools because they are funded by taxpayers' dollars. If the schools that had their semesters suspended were private institutions, then I would argue that--no--the government should not have that authority; but because the government sustains the schools that had their semesters suspended it does have that authority. On the other hand, it's not like the schools that had their semesters suspended could have continued operating if they wanted to; there were too many disruptions, with students interrupting classes and protesting. The protesting students even continued interrupting classes after Quebec courts issued injunctions, which should have allowed classes to resume. In many cases, the conditions made it impossible for teachers to continue teaching even if they wanted to.

Ok, now for part two--whether the government should have suspended the semesters of schools with protesting students. It is my opinion that the government should not have suspended the semesters, but should have cancelled the semesters. The students were not on strike, they had no obligation to attend school; they were simply protesting and they chose to protest; they voted to walk out of classes. No one forced the students to walk out and it is likely that teachers would have accommodated protesting students who wished to complete their semester, allowing them to hand in their assignments without going to class, but the protesting students were too focused on disrupting society and the economy to care about their education. It is as if the students were looking for an excuse to skip school, no matter how absurd that excuse was, and that's exactly what this protest was, an excuse to skip school, because the proposed hike in tuition was reasonable. Tuition in Quebec has been frozen for many years, as the tuition rates in the other provinces have increased, and today Quebec has the lowest tuition rate in Canada, a tuition rate that is substantially lower than each of the other provinces. The cost of my son's tuition here in Quebec is half of what my daughter paid in Nova Scotia. The condition and quality of a school is directly related to its funding; no tuition means no funding and no funding means decrepit conditions and low quality education. The protestors were behaving irrationally; it's a privilege to go to school and that privilege should have been suspended, not the semesters, but only for the students that chose to protest and only after their actions became destructive. Some may ask how the government was supposed to apply this idea; simple, alter the provisions that suspended the semesters and provided for a resumption date and alter them to measures that provided the students with an option: continue protesting and lose the semester, or return to school and complete the semester. Had the government chosen to take that path, although it may seem unreasonable to most, I am sure the students would have stopped protesting much earlier, saving the city much money and its people much aggravation.

Question:

You asserted that the protesting students should have lost their semester; do you think they should have been credited for their loss?

Anonymous:

No, they deserved to lose every penny; protesting was a choice and look at the cost the city incurred because of their demonstration. Only a portion of Quebec's student body chose to protest and the protesting students not only chose to protest, but they infringed upon the rights of the non-protesting students. The rest of the students, the one that chose not to boycott classes, were treated as if they didn't have the right to an education, an education which they paid for. It wasn't fair! The protesting students deserved to lose their semester, if not for any other reason, because they cost the dedicated students, the ones who didn't protest, their semesters. Even after dedicated students were given an injunction from Quebec courts to resume classes, the protesting students disregarded the court orders and continued preventing classes from resuming. The protesting students blatantly disregarded the law and they more-or-less got away with it.

On the other hand, the proposed increase in tuition was reasonable; the students in this province don't even pay one-quarter of the cost of their education, and they want to pay less. Without tuition fees, how are schools supposed to maintain their operations and facilities. If the students want cheaper education, then they are going to have to convince the rest of society to fund the educational system, which means substantially higher taxes for everyone in a province that is already heavily taxed. An alternative would be to tax those enrolled in academic institution substantially more, but then we arrive at the same problem; the students would complain that their education would result in substantial debt. The students weren't really thinking about what they were fighting for, it's simple economics; they were caught up in the mob's mentality. On top of that, look at how much they cost the city of Montreal in damages, in delays and in disruptions, without even considering how much the city spent on maintaining the police presence to ensure public security. The students weren't being civil; their protest weren't civil and their actions weren't civil; and even if the most sever incidents weren't the students, because they weren't willing to speak out against the criminal activity, they themselves discredited their movement.

Question:

According to the tenth provision of Bill 78, teachers were obliged to resume teaching classes on the day following the legislation of Bill 78 for institutions without suspended semesters; do you think that the government should have had the authority to oblige teachers to continue teaching under the circumstances?

Anonymous:

Just like the schools are funded by the government, teachers are paid by the government; if the teachers were working at private schools, then I would say no, but because they work in public schools and are paid by the taxpayers' dollars, I believe that the government should, as it did, have the authority to oblige teachers to return to teaching. And there was a provision that allowed teachers to go on strike if they so desired. Given the conditions were a bit shaky, with protesting students invading schools, but like I said before, someone has to consider the students that weren't protesting, and that's what this provision was doing. I also think that the provision that mentioned that teachers had to continue without slowing down their schedule was a reasonable provision, because it meant that students that were skipping class, to protest or otherwise, would suffer the consequence of their decision; although, I think that this provision would have made more sense had the government not suspended the semesters, but cancelled them. The protesting students got away with murder, metaphorically speaking. They infringed upon the rights of the non-protesting students, had their semesters suspended and got to finish them at no extra cost, while the non-protesting student who tried to go to class were forced to lose a part of their summer in order to finish their semesters, which they were forced to complete in a shorter amount of time than normally allotted. Sounds to me like the protestors won in the end. Truly, what transpired only served to show the protesting students that they can do this again and again without consequence.

Question:

What do you think about the provision--provision 14--that restricted demonstrations to more than 50 meters beyond the limits of school grounds?

Anonymous:

I think that the provision was legitimate. The demonstrations that took place around Quebec, like the one that happened at Dawson and UQAM, were disturbing the students that chose not to protest and disrupting schools that attempted to continue to provide instructional services. Blocking entrances to schools, disturbing classes, the students that didn't protest had the right to the education and their rights were being infringed upon by the protesting students. One persons' rights end where the next persons' rights begin; and the protesting students were not respecting the rights of the non-protesting students. On the other hand, school grounds are the government's property and the government has the right to protect its property. Many schools were damaged; look at what happened at the CEGEP of Old Montreal and in Gatineau, protesting students broke in and vandalized the schools, so now someone has to pay for the repairs and clearly it's not going to come out of the protesting student's pockets. If the students protested without damaging property--if they had handed out flyers instead of setting off fire extinguishers--then it is likely that this provision would not have been passed into legislation. Every provision in Bill 78 was legislated in direct response to some activity of the students; the protestors brought this Bill on themselves.

Question:

Do you think that provision 14 was a limitation of the freedom of association?

Anonymous:

Yes I do! But it wasn't an unreasonable limitation. The protesting students were using their freedom to associate to violate the rights of others. If you step on my shoes, you deserve to have your shoes stepped on too. This limitation on the freedom to associate was justified by the disruptive actions of the students. Protesting students stepped on the toes of other students so the government stepped on the toes of the protesting students. The problem is, the government didn't apply enough pressure; it passed the Bill into legislation but failed to impose it at every opportunity, and it should have. Had the Bill been applied as it was intended, much of the cost of the damages to the schools would have been paid for by the fines that the protesting students incurred, but the government used the Bill only in the most extreme cases, resorting to other legal provisions when possible. In my opinion, this was the government's biggest mistake, and it was an enormous mistake. Like I said before, had the Bill been applied as it was intended, then the protest might have ended earlier and much of the costs incurred by Montreal because of the protest could have been covered.

Question:

The third division of Bill 78--Provisions to Maintain Peace, Order, and Public Security--contended that, and I quote, "the organizer of a demonstration involving 50 people or more to take place in a venue accessible to the public must, not less than eight hours before the beginning of the demonstration, provide the following information in writing to the police force serving the territory where the demonstration is to take place: (1) the date, time, duration and venue of the demonstration as well as its route, if applicable; and (2) the means of transportation to be used for those purposes" (Bill 78 p7).

Do you believe that these restrictions were an unjustified limitation on the freedom of association?

Anonymous:

In normal times, this provision would be unjust because people have the right to demonstrate. The students had the right to demonstrate, but to demonstrate peacefully; in so much as you don't block the normal workings of the rest of the world, demonstrations can be an effective tool, but the students used them as a weapon instead and they overstepped their rights. Their marches disrupted the economy and their actions disrupted the public. In addition, these requirements would allow police forces to more easily supervise and direct the demonstrations. On top of that, the second requirement of this provision seem to have been legislated to facilitate demonstrations, in so much as the government appeared to be willing to complement public transit in order to transport the demonstrators to the events. On the other hand, look at how the students reacted to this provision; the students submitted a map of their intended route and it outlined a middle finger being raised on a single hand. Even after they submitted their route, they failed to stay on their proposed course; their map was intentionally drawn as a sign of disregard for the law and they intentionally left the proposed route to demonstrate their disobedience. It was becoming dangerous for the people who weren't involved in the protest; some individuals were even injured because they were caught between the police and protestors. By passing this provision into legislating, the government was protecting society, which is exactly what the laws are designed to do.

Question:

Division 5 was concerned with Penal Provisions. Section 26 of this division essentially asserts that any violation of the provisions in Bill 78 would result in "a fine of $1,000 to $5000"; unless the violation were committed by "by (...) a representative (...) of a student association (...) or by a natural person who is the organizer of a demonstration," in which case the fine would be "$7,000 to $35,000"; and if the violation were committed by "a student association (...) or a group that is the organizer of a demonstration," then the fine would be "$25,000 to $125,000" (Bill 78 p9). Furthermore, the fines would double "for a second or subsequent offence" (Bill 78 p9). Do you believe that these fines are overly harsh?

Anonymous:

These fines were severe, but--no--they weren't overly harsh. If you pass a law of this sort, if there are no serious consequences--in this case extensive fines--it's useless; so they needed the severity in order to show that they were sincere, but the government needed to actually impose these fines before they would be taken seriously. This Bill was passed because of a very strange set of circumstance; it's totally out of the ordinary, but it needed the harsh fines because without sever consequences there is no deterrent. I believe that the protesting students should have been brought to understand that education is a privilege, not a right; and fining each of the protesting students the amount suggested by this Bill each time they protest may have brought them to understand that fact. Unfortunately though, the provincial government did all it could to avoid imposing these fines. Nothing was reasonable about the entire circumstance. The students were unreasonable and their actions were countered with an unreasonable Bill. The seemingly unreasonable fines were justified by the unreasonable behavior of the protesting students. Yes, the Bill did in some way limit the constitutional right to freely associate, but it did so in light of the greater good--protecting the majority of society and guaranteeing the rights of others, others like you and me and those who disagreed with the position of the protesting students.

While Anonymous does present a controversial view, I must say I agree with her opinion; the protesting students were being unreasonable, both in their actions and in their desires. Not only did they disregard the legal system, but after violating several of its provisions, they sought to use it to defend themselves against a Bill that was only legislated as a result of the disruption and damage they caused. The protesting students cost Montreal very much money in damages, in disruption and in operations. Schools and properties were damaged in the demonstrations; citizens were inconvenienced on numerous occasions; and the cost of sustaining the police force required to govern the mass mob was substantial. Furthermore, the proposed increase in tuition was reasonable considering that tuition in Quebec has been frozen for nearly half a century, and considering that Quebec students pay only a fraction of the cost of their education. On the other hand, the provincial government failed to hold its position insofar as it failed to impose this Bill at every opportunity. The costs incurred by Montreal could have been obtained from the students though the imposition of Bill 78's fines. In essence, Bill 78 was unreasonable, but it was necessary; it was legislated in an emergency situation as a result of unreasonable action on the part of the protesting students. Had the students not damaged property, disrupted society or disregarded injunctions, but simply kept to demonstrating peacefully, then Bill 78 would have never been passed into legislation. Bill 78 is a creation of the protesting students, whether they accept that responsibility or not!

Works Cited

"37 arrested at Quebec student protests." 17th February 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/02/17/cegep-protest.html>.

"Bill 78." 18th May 2012. publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca. 28 November 2012 <http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca/dynamicSearch/telecharge.php?type=5&file=2012C12A.PDF>.

Canadian Press, The. "Quebec Student Protest Timeline." 24th May 2012. Huffingtonpost. 16th March 2013 <http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2012/05/22/quebec-student-protest-timeline_n_1537729.html>.

"Charest callls on student group to condemn vandalism." 16th April 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/04/16/montreal-vandalism-student-movement.html>.

"Emergency Quebec student law suspends semester." 16th May 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/05/16/quebec-students-do-not-want-special-law-return-to-class.html>.

"Masked student protesters storm Montreal classrooms." 16th May 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/05/16/montreal-student-strike-injuctions.html>.

"Massive Montreal rally ends with police clashes." 22nd May 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/05/22/montreal-day-100-student-strike.html>.

"Massive student tuition march paralyzes Montreal." 22nd March 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/03/22/montreal-student-protests.html>.

"Montreal bridge reopens after riot police move in." 23rd Feburary 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/02/23/montreal-student-protest-tuition.html>.

"Quebec adopts emergency law to end tuition crisis." 18th May 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/05/18/quebec-student-protest-law-bill-78.html>.

"Quebec college to remain closed after tense standoff." 15th May 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/05/15/student-protest-quebec-.html>.

"Quebec offers to stretch tuition hike over 7 years." 27th April 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2014 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/04/27/montreal-student-protests-quebec.html>.

"Quebec students stage massive tuition fee protest." 10th November 2011. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2011/11/10/quebec-tuition-strike.html>.

"Student protesters face fines after blocking Montreal traffic." 20th March 2012. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2012/03/20/student-protesters-champlain-bridge.html>.

"Tuition hike angers Quebec students." 18th March 2011. CBC News. 16th March 2013 <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/story/2011/03/18/quebec-budget-student-tuition-reaction.html>.

Leave a comment