Image Source: http://www.montrealgazette.com/news/frenglish/passion+local+language+Meet+some+people+have+become/7591482/story.html

Image Source: http://www.montrealgazette.com/news/frenglish/passion+local+language+Meet+some+people+have+become/7591482/story.html

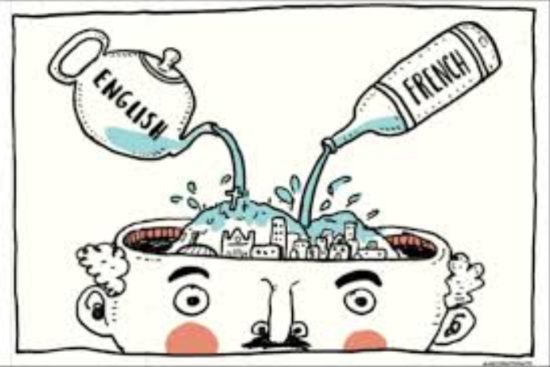

The evolvement of translation in Montreal has an intriguing history, featuring some amusing anecdotes pertaining to the evolution of the city`s first "dragomans". And it is important to note that being bilingual is not at all equivalent to being a quality translator; nor is it necessarily conducive to it, especially in the context of Montreal.

Put simply, when two languages overlap as much as English and French do in Montreal, there is plenty of room for such insidious things as calques, anglicisms and gallicisms (to name but a few) to creep in and yield negative impact on the quality of a translation. The usage of certain terms is always a bone of contention among language practitioners. For example, some of the first famous French-Canadian translators and interpreters would often "accuse" each other of using random anglicisms! That, however, did not at all mean that some of them were less professional than others; rather, it is testimony to the presence of a continuous anglo-franco fusion dating back to the dawn of the translation industry in Montreal.

Historical Highlights

Official translation in Canada dates back to the XVIII century. Its first stage was inaugurated, in 1710, by the launch of parliementary debates on Parliament Hill, starting off after the Confederation. Initially, there were few linguistic reference works and no automated translation tools to work with, which practically left the early artisans of translation with a whole host of items whose foundations were yet to be laid.

Up until the centralization of translation services (1867-1934), crowned by the creation of the Translation Bureau, the sphere of translation was going through what many consider its "golden age"; Hector Carbonneau, who was the head of the General Translation Services for over thirty years, came up with the apt qualification. The "golden age" of translation in Canada implies the initial stage in the development of the domain, wherein translators were not numerous and knew each other fairly well, which generated an intimate atmosphere for tranquil collaboration. The vast majority of them were French Canadians who would meet up at various events organized by literary, cultural and professional companies.

It is fair to note that, Quebec, within Canada, has always been in a privileged position in terms of translating. Canada`s bilingualism secures translators a really well-established market; and that is due primarily to two factors: the creation of the Translation Bureau in 1934 and the adoption of the Charter of the French Language in 1976. The former was set up to serve the purposes of all federal ministries; the latter was meant to assure the primacy of the French language in Quebec (in advertising, education and the professional environment). Federal government departments need to translate everything, and three quarters of the overall translation is done into French. What that means is that, since 17% of all translation in the country is done within the public sector and all federal documentation must officially be translated into French, translators are not short of work most of the time. In Quebec, whenever a foreign company wants to establish itself within the local market, it has to work in French, which leads to hiring translators.

The First Artisans of Translation

The first translators were primarily men and women of letters; and those who practised literary translation, in particular, did so mainly to perfect their writing skills - literary translation has always been considered a writing prep par excellence. Interestingly, since religious issues were in the air at the time, those people were often either ardent believers, indomitable atheists or fierce anticlericalists. Their ideological views were thus very different. That, however, did not prevent them from getting together for the sake of professional interest. Although some of them did not have the best of relationships, those erudites constituted quite a homogenous circle of translators, marked by a harmonious co-existence.

The first instances of official translation are found in Ottawa. Thus, the first notable figures of the initial translation "wave" mainly enaged in parliamentary and administrative paperwork.The better part of the first translators were professional writers, poets and journalists whose creativity ignited the literary and cultural life in the capital. In the same breath, Ottawa owes them the development of its professional life which they significantly contributed to: the first two associations of translators, the Cercle des traducteurs des livres bleus (1919) and the Association technologique de langue française d`Ottawa (1920) as well as the foundation of the first translation courses were set up by the linguistic and literary elite of the time.

On the other hand, evidence has it that linguistic issues would sometimes still cause translators to exchange quite pungent remarks, which, by the by, proved their sharp wit and nimble perception. For instance, famous Quebec writer and journalist Rodolph Girard would once have a minor altercation with another, not less famous, author and translator Pierre Daviault as regards anglicisms. The former got accused by the latter of using an anglicism in his speech: "My dear fellow, you are committing an anglicism." - "I would like you to know, my learned colleague, that I know my French." - "Your French? Obviously. But it`s standard French you should know ." Ironically, that same Pierre Daviault, whose repartee was, no doubt, brilliant, was once also taken down a peg or two by his another colleague whom he had the imprudence to pick upon. It was translator Ernest Plante, who retorted with a quick-witted rejoinder to Daviault`s pointing out that he had used a rare word: "The dictionary indicates that the word you used in your translation is rare." - "I know; that`s why I rarely use it." Apparently, those translators were nothing short of witty!

On the Cusp

That funny anecdote showcasing translation professionals getting under each other`s skin for the sake of linguistic accuracy speaks volumes about the omnipresence of the fine line separating French from English in the context of Quebec. But what about Montreal? This city is not only bilingual - it is hugely cosmopolitan, which rightly sets it apart from the rest of Quebec. On the one hand, the mutual influence of English and French in Montreal goes as far as to have anglophones and francophones not only use anglicisms and gallicisms respectively in their speech and writing but also, importantly, copy each other`s grammar and syntax. On the other hand, Montreal teems with numerous multi-national and multi-cultural groups which, in some way, shape the city`s inner structure and might also influence the way English and French are used. To top it all, representatives of those groups also often engage in translation studies, bringing in new colours and shades to the process of language transfer. How obnoxious can all those factors be for translation, wherein each language must, by definition, be void of any incongruent admixtures from other languages?

Of course, it is fair to note that within the linguistic community of Montreal, specifically, a translation of, say, instructions, containing anglicisms, gallicisms or structures that are grammatically correct as such but do not really sound English to anglophones and French to francophones may be tolerable - locals, being, for the most part, bilingual will not have difficulty understanding the message (what they will think of such a translation, if they happen to be grammarians, is another thing, though). On the contrary, should the English translation of a certain document travel to the U.S. or England, for example, and the French one to France or southern Belgium, the company having produced them will most likely miss the mark. Mixed-up structures and turns of phrase are faulty and awkward and language-literate readers are in their full right to regard them as mistakes and, well, lambaste them.

"Mistakes are probably not something you strive for. Some mistranslations are funny, while others are viewed as rude, inconsiderate or just downright offensive and unprofessional. It's all about image - and people want to buy from a company that has a positive one. So it stands to reason that if your organization comes off as unprofessional, inadequate or a joke, your customers may decide to take their business elsewhere. Don't make your company the punch line or the enemy by publishing less than perfect translations or not doing your research. After all - a mistake that people notice can mean unwelcome and embarrassing attention." (www.sajan.com/translation-quality-why-you-cant-afford-any-mistakes).

To illustrate some of the most common French-to-English translation snares and pitfalls, particularly waylaying translators working within a bilingual community (like that of Montreal), it is easiest to just cite the most wide-spread examples of the so-called false friends (faux amis), which can also be regarded as anglicisms or gallicisms in certain cases. Let`s consider, say, "intervention" - the word`s spelling is absolutely identical in both English and French. However, translating "intervention" from French, a good translator will scarcely ever use the word`s homonymous counterpart in English. In French, "intervention" has a number of meanings and is used literally everywhere in government documentation; it is part of the vocabulary often referred to as "officialese".

If you look it up in a bilingual dictionary, you will find "intervention" in English as the first direct equivalent of the French "intervention": http://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais-anglais/intervention/43810.However, even in the examples provided by the dictionary, you can clearly see that the translation of the word in context turns out different and has other equivalents in English - "intervention" can thus also be translated by "speech", "statement", "contribution", "investment" or "participation" depending on the context. Notwithstanding that variety of choice, a lot of anglophone translators whose English linguistic resources are "overpowered" by French often do not render the semantic nuances that may be absent in the French version but must be inferred from context and reflected in the English one.

Funnily enough, non-native speakers often have the upper hand over native-speakers in terms of grammatical and syntactic accuracy - if they did not learn English and French in Montreal, of course. At home, they usually learn the standard version of a foreign language, uncontaminated, so to speak, with pests of language that loanwords and calques can be. Not to forget that they might be somewhat influenced by their own language, though; but still, they are often more alarmed to the grammaticality of a language that is foreign to them - native speakers tend to take their language for granted. Why? Because it is their mother tongue and they, naturally, feel like they are in the position to take liberties with it. Sometimes those liberties may lead to innovative language forms that enrich the language and take it a couple of steps further as regards versatility and flexibility; oftentimes, however, they result in illiterate distortions which are so deleterious for the language of the younger generation who momentarily absorb incorrect forms and use them ignorantly as if they were the opposite. Everyone makes mistakes. And they may even be pardonnable to most; less so for translators, though. Remember Pierre Daviault and company? There you go....

Sources:

www.tradulex.com/articles/Cohen.pdf

www.sajan.com/translation-quality-why-you-cant-afford-any-mistakes

Your picture says it all. Very interesting read!